The era of declining global poverty is over

Global development is hitting a wall

A few days ago, Our World in Data published what I think might be the most important article written this year. It’s a short piece by the site’s founder and editor, Max Roser, and it has a rather ominous title: “The end of progress against extreme poverty?” The piece is absolutely worth reading, because it drives home a point that I think will become an extremely important fact about this century, which is that progress in reducing extreme poverty globally is hitting a wall. The rate of extreme poverty reduction is decelerating; and within a few years the share of the global population living in extreme poverty will begin to increase.

In Roser’s words:

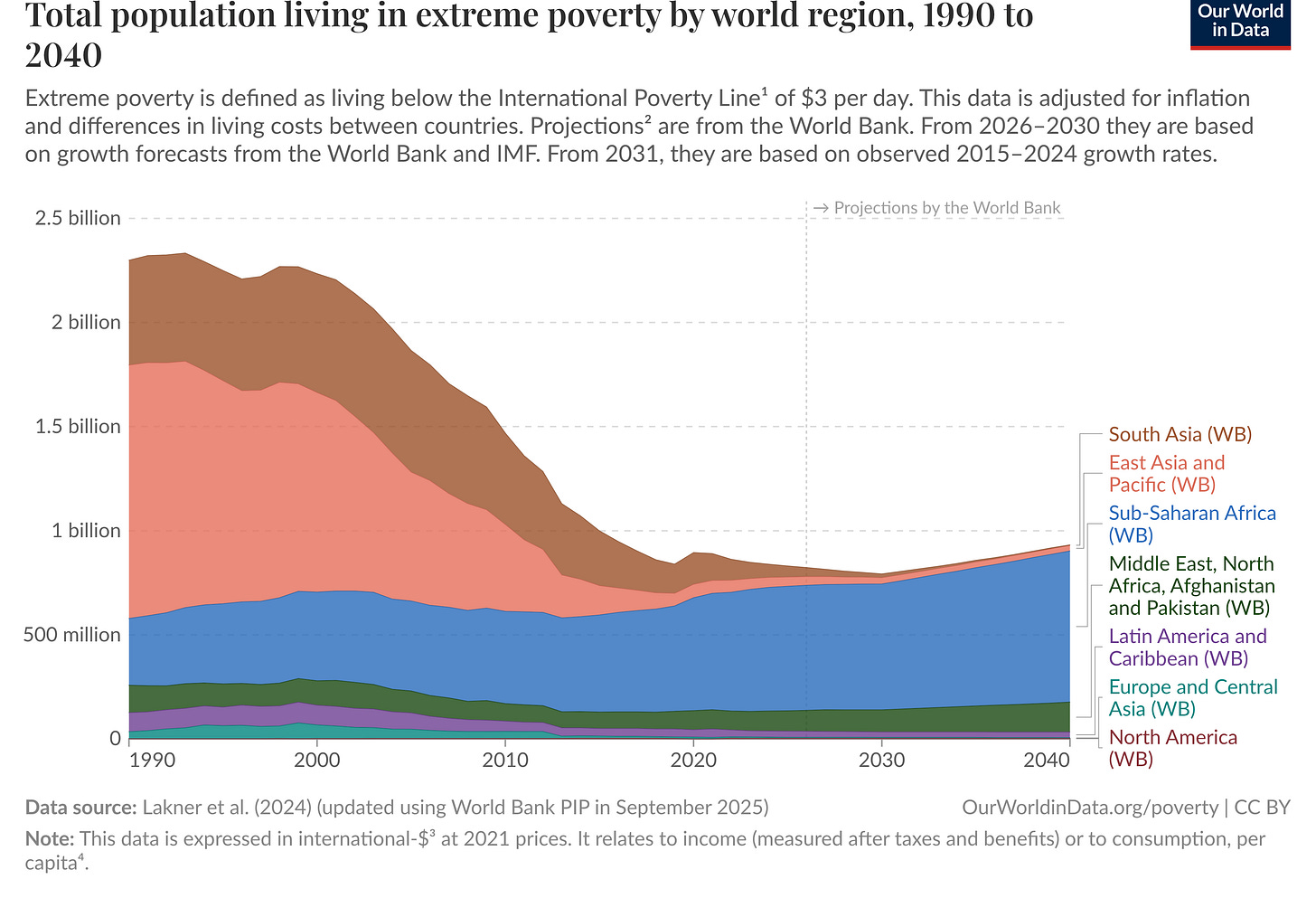

In the last decades, the world has made fantastic progress against extreme poverty. In 1990, 2.3 billion people lived in extreme poverty. Since then, the number of extremely poor people has declined by 1.5 billion people. …

Can we expect this rapid progress to continue?

Unfortunately, we cannot. Based on current trends, progress against extreme poverty will come to a halt. As we’ll see, the number of people in extreme poverty is projected to decline, from 831 million people in 2025 to 793 million people in 2030. After 2030, the number of extremely poor people is expected to increase. Based on current trends, progress against extreme poverty will come to a halt. …

I’m always skeptical when people say that we are at a juncture in history where the future looks much different than the past. But when it comes to the fight against extreme poverty, I fear it is true.

As Roser writes later in the article, the dynamics underlying the coming increase in global poverty are relatively simple. The last few decades have witnessed strong economic growth in a number of countries that were, forty or fifty years ago, extremely poor; thus the total number of people in poverty has declined precipitously along with the share of the global population that lives in poverty. But now the majority of people in “extreme poverty,” defined as earning less than $3 a day, live in a set of countries that have exhibited very little growth over the last few decades. These include most African nations along with such troubled spots as Afghanistan, Yemen, and Haiti.

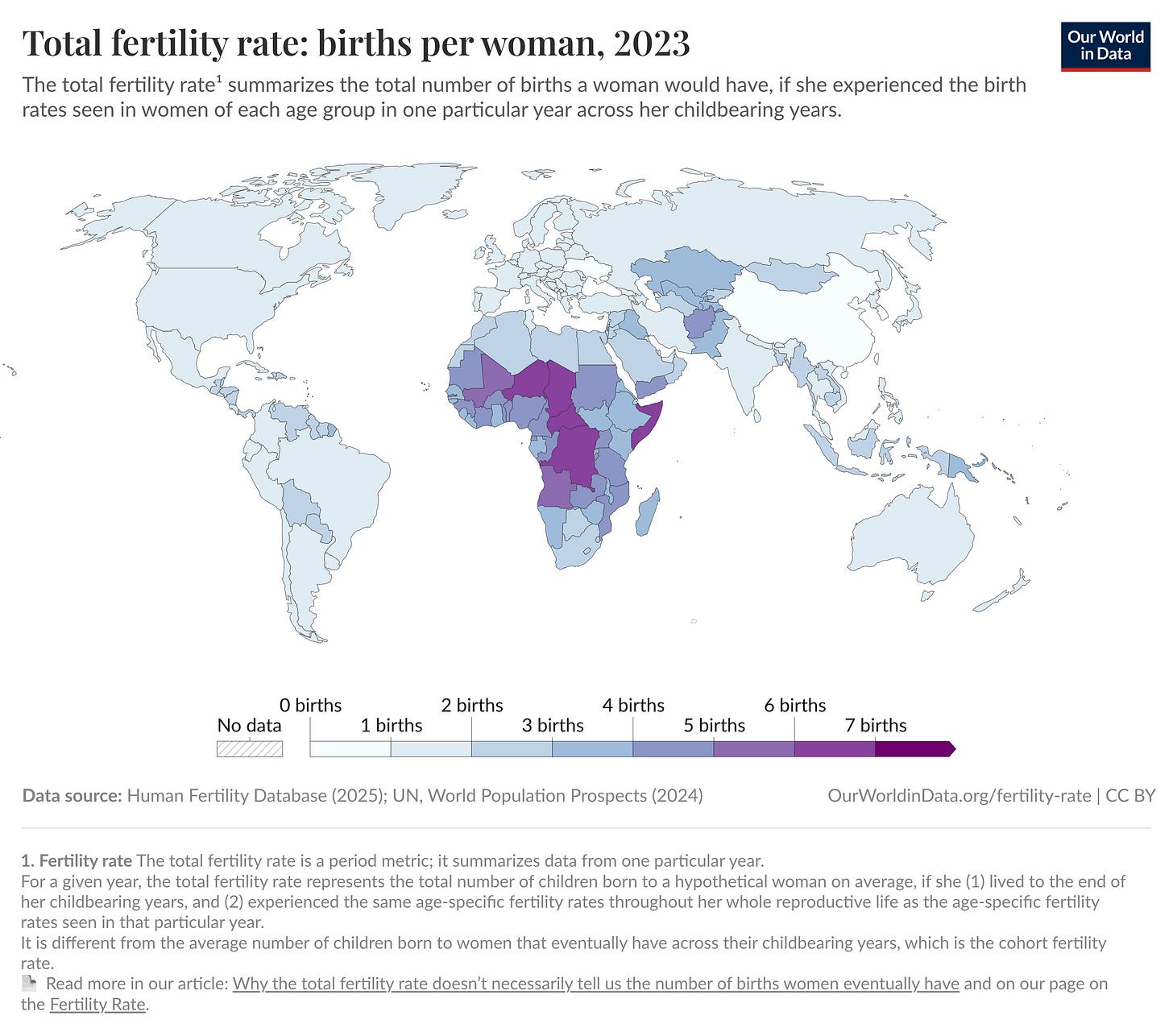

Meanwhile, we are in the midst of a global demographic transition. Fertility rates have fallen precipitously not only in the rich world but also in virtually any country that has exhibited some degree of development: even countries like India and Bangladesh, which are still quite poor, have seen their fertility rates drop to sub-replacement levels. Thus populations in much of the world are set to decline. Europe’s population is already declining; the populations of Asia and Latin America are set to begin declining in the 2050s.

But the poorest nations in the world, concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa, have not experienced this fertility transition. In these societies, in fact, the combination of persistently high fertility with declining mortality (thanks to the global diffusion of medicine over the last few decades) has created the most spectacular population boom in history. In 1970, Africa had 366 million people and 10 percent of the world’s population; by 2070, 45 years from today, the United Nations projects that it will have 3.15 billion people and 31 percent of the world’s population. Even within Africa population growth will be concentrated in the poorest and worst-off places: countries like Sudan, Mali, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo will grow their populations several-fold in the decades to come. Assuming that those countries don’t make rapid progress against poverty and that fertility rates in these places do not suddenly collapse, the growth of these very poor places means that global extreme poverty will necessarily increase.

This is essentially the outcome that my friend Henry Williams and I predicted in a 2022 article for American Affairs on “the long, slow death of global development”:

With the global population outside of Africa entering a long era of slow growth or decline, and African population in the midst of a long and spectacular boom, the future of development and poverty reduction will hinge on the future of Africa. In the past, the exceptionally strong performances of East Asian economies have statistically compensated for less impressive results elsewhere, especially among the African economies—many of which, despite improvements in health, cannot be said to be meaningfully richer or more economically developed now than they were in 1980. But as East Asian populations decline, the intercontinental compensation effect in poverty reduction statistics will no longer hold. And because there has been so little real economic progress in sub-Saharan Africa, rapid population growth will spell a grim several decades for “poverty reduction,” and for development in general.

At the time, that was something of a controversial view; the blogger Noah Smith, for example, argued that in fact “economic development is doing OK,” and that poor countries are “catching up faster than before.” But I think that Roser’s article is a good indication that over the last few years a lot of people more inclined to optimism about poverty reduction have come around to the view that global economic development is not, in fact, “doing OK,” and that there is very good reason to be concerned about what is happening in the poor world.

Of course, this relatively pessimistic view of the situation—that over the next few decades Africa will largely stay poor, that its population will grow tremendously, and that this will lead to rising global poverty—relies on two assumptions: namely, that economic growth in Africa will not improve and that African fertility will not experience a rapid decline. Both are worth interrogating.

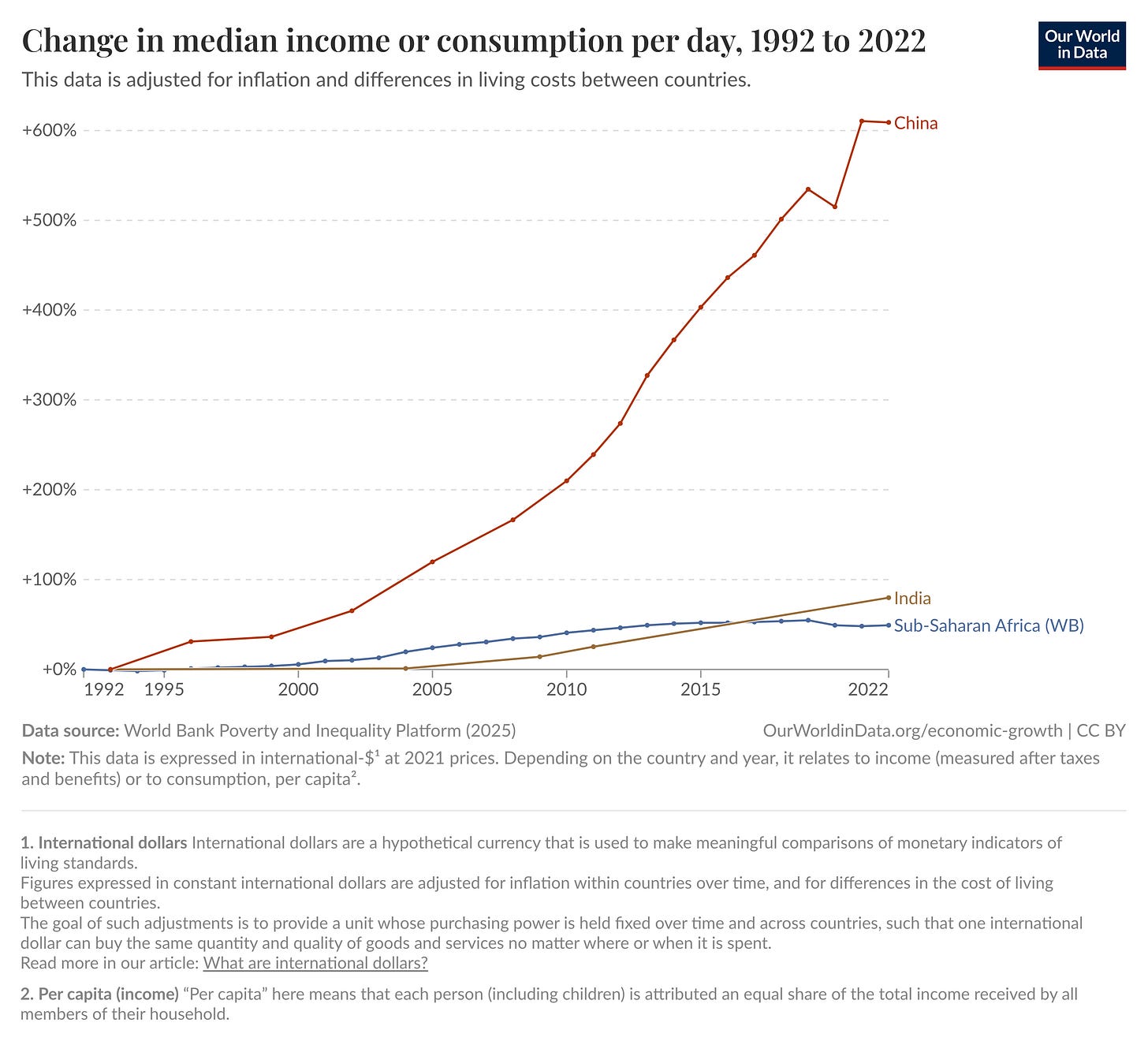

The basic reason why I’m not very optimistic about Africa’s growth prospects under current conditions is that the track record is extremely poor, and there’s little reason to think that anything fundamental has changed. Between 1992 and 2022, median income in China grew at an average annualized rate of 20 percent per year; in India it grew at a rate of 3 percent per year; but in sub-Saharan Africa it grew at just 1.6 percent per year, less than the rate of growth exhibited in the famously stagnant (and much wealthier) United Kingdom. But in much of the continent the picture has been worse than mere slow growth. Some countries that were relatively stable a few decades ago are now in a state of apparently permanent civil conflict, as in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) or Somalia; while other countries that have been blessed by relative stability, such as Kenya, Malawi, or Zambia, are poorer on a median income basis than they were in the ‘80s or ‘90s.

There are many things to say about why economic growth in Africa has been so disappointing, from the primacy of extractive resource sectors to the dominance of predatory elites to the poor state of human capital to the ubiquity of corruption to the absence, in many places, of a strong state monopoly on legitimate violence. But these are merely surface-level problems: the fact that these conditions exist in nearly every country in Africa, despite their widely varying historical experiences and the different ideologies with which their states have experimented, suggests that the fundamental problem is not so much with the state but the society underlying the state. If you were to describe this problem briefly, you could do quite well with something like “kinship groups crowd out effective institutions.” African societies have extraordinarily strong kinship ties, such that impersonal institutions and relationships are systematically subordinated to family, clan, and ethnic loyalties; as a result many African societies have found it extraordinarily difficult to build effective states and civil societies that are capable of doing what states and civil societies are supposed to do. (For a more complete elaboration of this view, see my article on why African nations don’t have large firms.) Solving that problem took Europe roughly a millennium; and that was when subjects did not have access to AK-47s.

So if African growth cannot be expected to improve anytime soon, what can be said of African population growth? Here we enter more speculative territory. In recent years, there have been claims that African fertility is “plummeting” faster than projections have indicated, with the implication that the African population boom might not be as massive as demographers believe and “even Africa will fall to the low-fertility trend soon.” And indeed fertility in some African nations, most prominently Nigeria, has fallen faster than was expected a few years ago: in 2024 the United Nations projected that in its “medium fertility” scenario Nigeria would have 359 million people by 2050, compared to its 2015 projection of 399 million people. There have been similar downward revisions for Kenya, Burundi, Uganda, Zambia, Niger, and a few other places.

But these downward revisions have been largely balanced out by upward revisions for other countries: the UN’s current projection for the DRC, for instance, expects 218 million people by 2050, compared to its 2015 projection of 195 million people. In many African countries fertility decline has been slower than what the UN had expected a few years ago. Ethiopia’s projection has been revised upward by 37 million people; Somalia’s by 10 million; Angola’s by nine million; the Ivory Coast’s by seven million; Sudan’s by five million. Some projections were too high; some were too low; but broadly fertility decline in Africa has occurred as the UN’s demographers predicted and the updates have been minor. In 2015 the UN projected that sub-Saharan Africa would have 2.12 billion people by 2050; it now projects that it will have 2.09 billion people by 2050, a difference of just 30 million. The UN demographers know what they’re doing.

So we probably should trust the African population projections. Fertility decline is a very gradual process, especially when it does not occur with the heavy encouragement of muscular states; and it is especially gradual in rural societies still governed by traditional mores, as in much of Africa. There is no reason to expect a rapid collapse in African fertility rates. By this point there is enough population growth baked in, enough “population momentum,” that it would take probably the most dramatic fertility reduction in human history, rivaled only by that which China experienced in a single generation between 1965 and 1985, for the population projections for the 20-odd years to be wildly off-track.

So if you want a picture of the future of the world population, you need merely look at where people are being born today. The numbers aren’t happy ones. Last year, Somalia had more births than Spain and Italy put together; Sudan had more births than Germany and France combined; there were more births across Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Yemen than in all of China; there were 1.1 million more people born in the Democratic Republic of the Congo than in the entirety of the European Union. The future will look different from the past.

The upshot of all this—the poorest places haven’t gotten richer, and they will add a lot more people in the decades to come—is very alarming. It might be that in the near future the rich countries of the world unlock the benefits promised by artificial intelligence, robotics, and other advanced technologies, and that this creates a new period of rapid growth that further enriches the rich and perhaps enriches the poor world along with it; perhaps self-bootstrapping artificial intelligences will unlock stages of civilization so grand as to make the present-day problem of extreme poverty seem quaint and inconsequential. But we cannot count on such deus ex machina outcomes. The world implied by our default trajectory is very bleak.

It would be a mistake for people in the richer corners of the earth to think that they would be immune from the problems and pressures that such an outcome would create. The migration crises of the last few years, with all the social and political dislocations they caused throughout the West, would look like small dramas compared to the crises of this world.

The great economist Robert Lucas once wrote that the consequences for human welfare involved in questions about economic growth in poor countries were so staggering that “once one starts to think about them, it is hard to think about anything else.” I think about that quote a lot when it comes to the question of what is happening now. The stakes are so significant that once you think seriously about them it becomes hard to think about anything else.