Africa doesn't have large firms because it doesn't have social trust

On the causes of informality in African economies

The political scientist Ken Opalo, who writes at his blog An Africanist Perspective, had an interesting post yesterday called “There will be no economic takeoff in Africa without lots of large (private sector) firms.” The piece is worth reading. The gist is as follows:

African nations have an extremely severe problem of underemployment. There are far fewer jobs than there are people trying to get those jobs, so there is a tremendous amount of unemployment and underemployment that shows up as employment in the “informal sector.” Work in the “informal sector” basically amounts to subsistence labor that masks unemployment.

African governments have tried to deal with this surplus of labor by encouraging migration abroad and by encouraging people to return to agriculture. Neither of these strategies have worked.

African governments should instead encourage the formation of larger and more formal firms, which are “an amazingly efficient way of organizing economic activity.” Large formal firms are more efficient than small informal ones; they provide better jobs, they boost state capacity, and are simply better for growth. Empirically, the more developed a country the more formalized its firms.

Therefore African governments should implement a policy agenda to foster the development of larger firms: “Policy interventions that might work include lowering the cost of doing business and getting big, active government support of young domestic firms, cultivating financial systems that provides longer runways for young firms, and an ideational commitment to modernization and rationalization as critical to organizing economic activities.”

Opalo is obviously right that rich countries tend to have more formalized economies than poor countries. There are some confounding variables—post-Communist countries like Ukraine or Bosnia tend to have more formal economies than one would predict based on their level of income—but in general it’s true that a defining characteristic of poor countries is that a lot of people are “informally employed” and that there are relatively few large firms like one encounters regularly in the United States, Europe, or East Asia.

So is “deliberately shepherding the process of increasing firm sizes and the number of employees per firm,” as Opalo suggests, the right strategy? Here I think he confuses symptom for disease. Yes, sub-Saharan African countries have very few large firms. But the reason they do not have large firms is not a “decades-long fixation with informal micro-entrepreneurship” by governments and NGOs. African countries don’t have large firms because they have extremely low levels of social trust, which makes the complex economic arrangements on which large firms necessarily rely extraordinarily difficult. A strategy of seeking to increase the average size of firms because rich countries tend to have larger firms is like seeking to build more skyscrapers because rich cities have more skyscrapers. It’s getting the causal structure wrong.

The birth of the corporation as a social form in northern Europe—as distinct from the “family business”—was a product of a social revolution that had been unfolding for hundreds of years. In traditional societies, economic cooperation is largely confined to family and kin networks, because social trust is scarce and enforcement mechanisms are weak. The corporation, by contrast, is based on a legal and social architecture that requires people to submit to abstract legal frameworks, contractual obligations, and institutional guarantees. This requires rule of law and strong state capacity, but also a social order in which people are willing to trust and cooperate with strangers, accept the legitimacy of impersonal institutions, and subordinate kinship loyalties to legal obligations.

This is a very high bar, which is why the social form of the corporation could only really flower among the Protestant bourgeois of cities like London and Amsterdam. Simple commercial arrangements like a forward contract or a check—an implicit promise that one has a given amount of money in a third-party institution called a bank, that this bank will have the money available when the counterparty shows up to collect it, and that if something fails there is proper recourse—reflect an extraordinarily high degree of social trust.

That is why societies with low levels of social trust—by which I mean the willingness to trust and cooperate with people outside one’s kinship group—tend also to have smaller firm sizes as well as more informal economic arrangements: less money in banks, lower levels of credit, and fewer formal labor contracts. Simply put, it’s very difficult to operate a large formal business if the enforceability of contracts is a matter of doubt in any way or if personal relationships and affiliations are seen to supersede legal ones. Rule of law doesn’t need to be absolute, and there was plenty of corruption and chicanery in the United States and East Asia during their periods of most rapid industrial expansion. But the ability of everyday legal agreements to be promptly enforced is an absolute requirement for firms to scale.

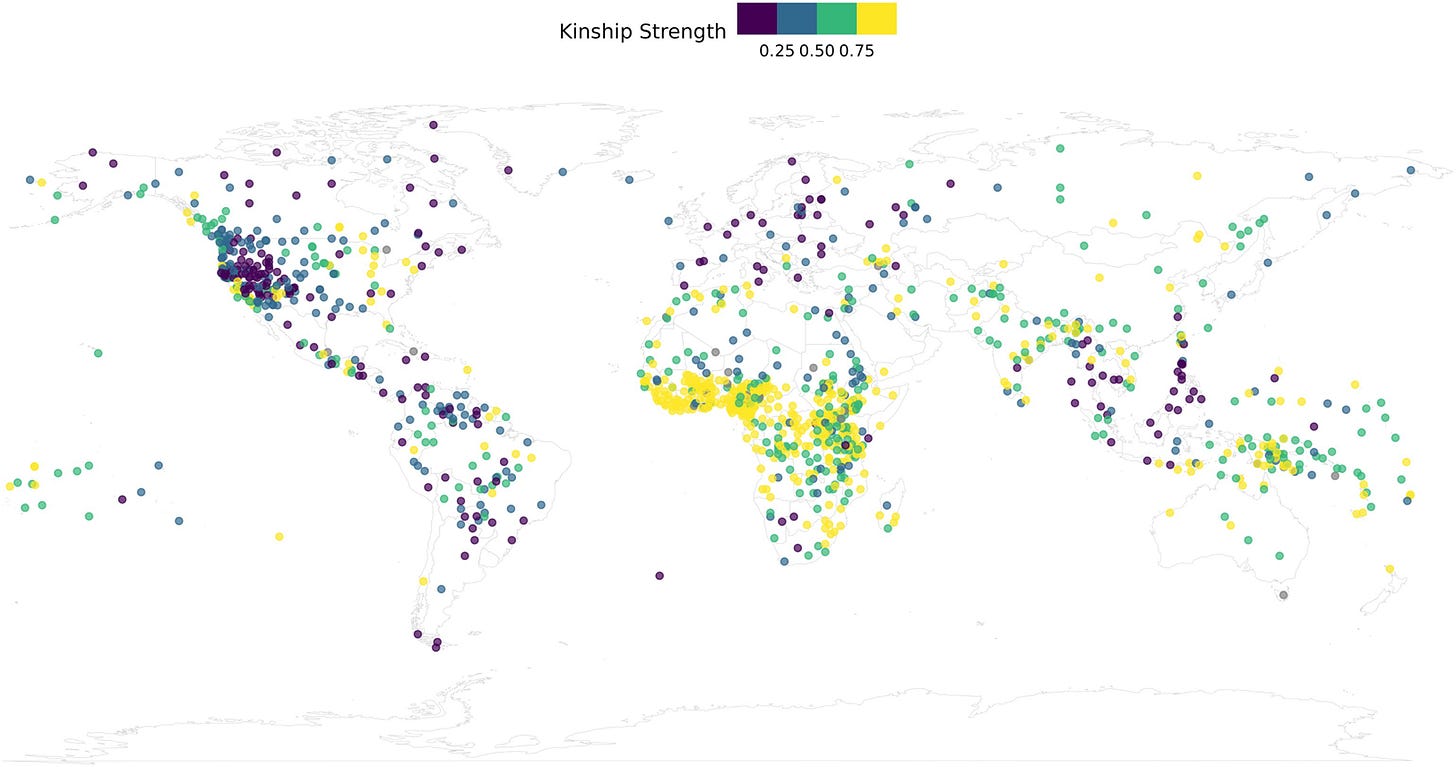

In turn the reason that African countries have so few large firms, and in part why African commercial economies tend to be so inefficient and have such high transaction costs, is that they have extraordinarily low levels of social trust. In practically every African country, impersonal social trust as measured by the World Values Survey or Afrobarometer ranks among the lowest in the world. Meanwhile kinship intensity, as measured by the strength of various kinship-favoring norms—preferences for cousin-marriage, polygamy, the co-residence of extended families, clan organization, and community endogamy—is extraordinarily intense across Africa. The Ethnographic Atlas dataset, recently validated by Joseph Henrich, suggests that African societies in fact have the strongest kinship ties in the world.

As one would expect, all the economic symptoms of the lack of impersonal trust and dependence on kin networks that are embedded in traditional societies—the absence of forward contracts, the avoidance of the legal system in handling commercial disputes, the inability of ethnically mixed groups to punish defectors—are abundant across Africa. It is this stark deficit of impersonal and out-of-network trust that prevents African societies from forming large-scale, complex, formal enterprises; large firms rely on contractual obligations—to and from employees, suppliers, and customers—that cannot be enforced in a situation where kinship ties outweigh impersonal obligations. It is this trust deficit that leaves an opening for market-dominant minorities, like Lebanese in West Africa or South Asians in East Africa, to fill the vacuum. It is simply not possible for societies to develop large and efficient enterprises if they do not have a baseline degree of impersonal social trust; without that baseline degree of trust enterprises remain confined to kinship networks, with all the inefficiencies that they bring.

The abiding strength of kinship ties relative to impersonal commitments to a company or to a state remains the central weakness of African societies. The absence of large firms in African economies is simply a symptom of this broader weakness. It might be helpful for African governments to take a less rosy view of informal “micro-enterprises” and evaluate jobs programs on the basis of “how much they foster the growth in firm sizes and the overall share of formal sector employment,” as Opalo suggests. But the limiting factor preventing the formation of large firms in Africa is that African societies simply lack the requisite degree of impersonal social trust for them to take root.

Good post.

But I think “trust” is overrated as an explanatory variable. Trust beyond closed groups is endogenous to the capacity to enforce contracts at scale - so you need scalable social institutions (religion) or states. Notice that early modern corporations often has explicit sovereign backing. They didn’t just spontaneously spring from social trust.

Another important point is that there are indeed a lot of firms in Africa that operate at scale. The point of ny piece is that the region needs more of these, and that they should be bigger.

Shouldn't some sprawling rich families be able to make conglomerates that are still kin network affairs, but employ lots of people?

Thinking of the Ayala family in the Philippines (Ayala malls, San Miguel corp and much more), or the chaebols in Korea (Samsung, LG, Hyundai) and zaibatsu in Japan (Sumitomo, Mitsubishi). I believe similar dynamics have happened in a large number of other countries (without a ton of additional research, I'd guess that Tata, Vingroup, and Thaibev all fit the pattern too).

All of those families employ hundreds of thousands of people through their businesses, but they're still kin network affairs at the top to a pretty large degree, even today, and moreso in the past. I don't see why this model couldn't also work in Africa?

It's the common pattern in a lot of developing countries, even those lower on capital and specialization and "rule of law" when the companies got started.