Why poor countries stopped catching up

The rise and fall of the Great Convergence

At the very tail end of 2025, three economists published an essay that I think qualifies as a strong late entrant for “most important essay written in 2025.” By the rather sedate standards of economics, it was the closest thing to a bombshell: a mea culpa from high up in the profession. They gave their essay a blunt title: “We were wrong about convergence.”

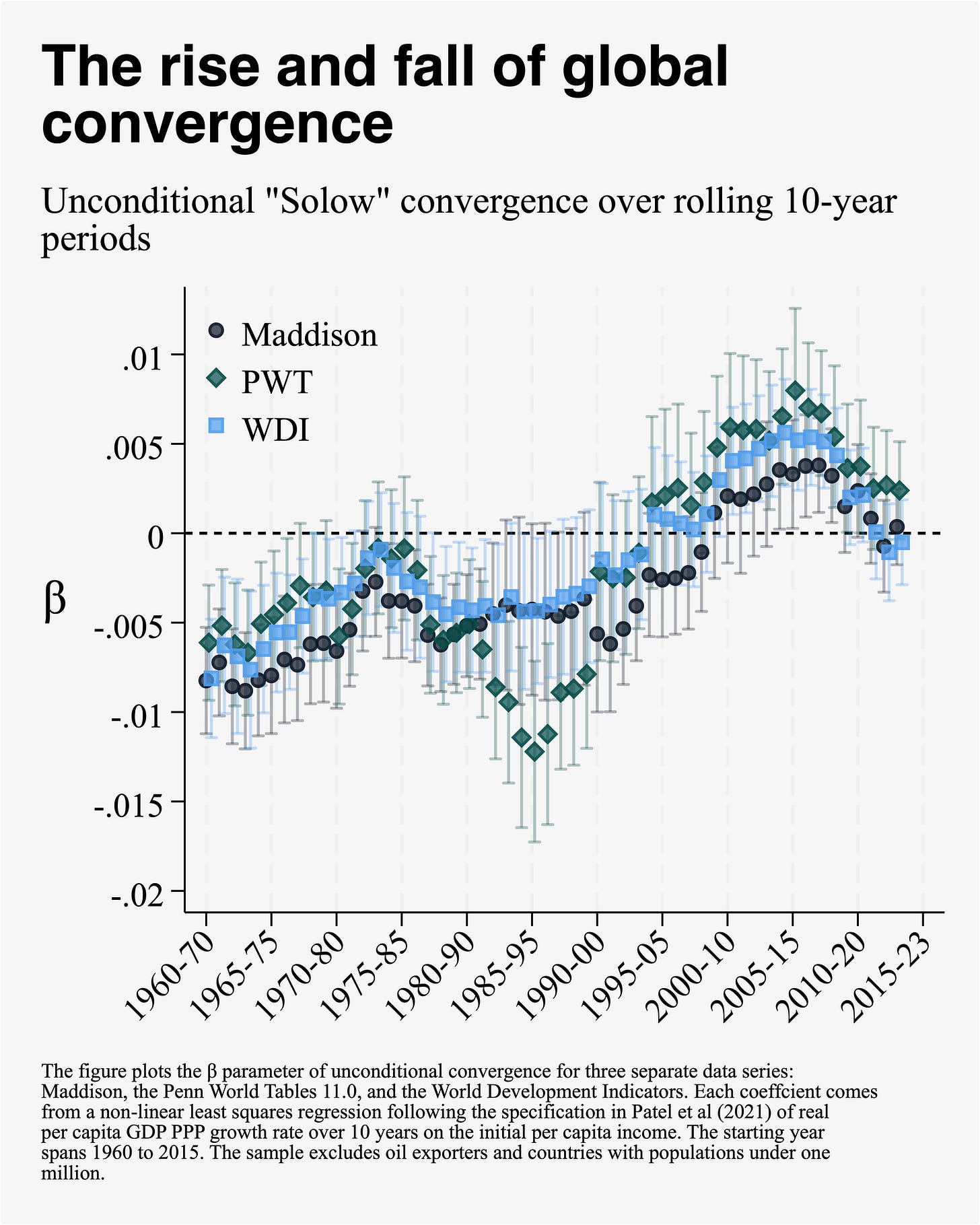

Some context is needed. A few years ago, these three economists—Arvind Subramanian, Justin Sandefur, and Dev Patel (we can call them SS&P for short)—published an important empirical finding about how poor countries were doing relative to rich ones. For a long time, economists had been troubled by a difficult fact. Economic theory predicts that poor countries are supposed to grow faster than rich countries. “Catch-up growth” resulting in “economic convergence” is a straightforward prediction of the Solow-Swan growth model, and the Solow-Swan growth model is one of the central ideas in all of economic thought. But in reality this wasn’t happening. “Solow convergence” was never seen in the wild. If anything, the gap between rich countries and poor ones was growing.

Then, in the late 2010s, SS&P made their announcement. Sometime around 1995, they found, the trend had reversed, and rich-poor convergence had finally come alive: poor countries had started catching up to rich countries. Solow convergence had arrived at last. It was, they announced in a 2021 paper formalizing their finding, “the new era of unconditional convergence.”

At the time, this finding was widely celebrated. The popular blogger Noah Smith went so far as to announce that the SS&P paper constituted his “basic theory of development.” In the past, he said, poor countries were failing to outgrow rich ones because of unfortunate circumstances (“the war, bad policies, and dysfunctional institutions that afflicted developing nations in the mid-20th century”). Now that those were swept away—they were, he said, merely a “temporary phenomenon”—the catch-up growth that economic theory predicted had finally arrived. Globalization was working; development was succeeding; the gap between rich and poor countries was closing. So there was tremendous reason for optimism about the future.

Now, a few short years later, SS&P have returned, hat in hand, to say that they were wrong. The era of convergence that they heralded in 2021 was over almost as soon as it started. Poor countries are once again growing slower than richer ones. “The facts have changed again,” they write. “Unconditional convergence appears to have come to an end.”

A short history of (non)convergence

What is convergence? Why does economic theory expect that poor places are supposed to grow faster than rich ones?

For that, we should start with the great economist Robert Solow. In 1956, Solow published a seminal paper, titled “A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth.” Solow proposed that there are three factors that can explain long-run economic growth. Capital accumulation is one. The growth of the labor force is another. And the third is weirder: a “residual” element, which Solow and his followers attributed to technological innovation and productivity growth. (This is the “Solow residual.”)

Let’s focus, though, just on capital. The size of the labor force and the contribution of the “residual” don’t change much day to day. The key thing about capital, you’ll notice, is that it has diminishing returns. If you’re building a factory, then you’ll find that your first production line will have a huge marginal contribution. Your fifth will have a big one too. But by the time you reach your hundredth production line, or your thousandth, diminishing marginal returns will have kicked in. Eventually the marginal return will have diminished to zero.

This is interesting and important in itself, of course, but there’s an important implication. If the marginal return to capital is always falling, then at any given time—any given population, any given level of technological achievement—any given economy will have a certain point at which the marginal unit of capital won’t do anything. This is the steady-state equilibrium of the economy. We can think of economic growth as the process of moving closer and closer to that frontier. Over time, that frontier moves. But it usually doesn’t move dramatically from one year to the next.

And this has another interesting implication. Certain places are closer to the frontier than others, and in the places that are closer to the frontier diminishing marginal returns have really begun to bite. And so, all else being equal, we should expect to see poor countries grow faster than rich ones. (All else being equal is crucial. We’ll return to it later.) We can say this as “there’s more low-hanging fruit,” or “the marginal return to capital investment is higher,” but it’s all the same idea.

And so the Solow model predicts, pretty straightforwardly, that poor economies will tend to grow faster than rich ones, and the rate of growth will slow as they get richer. This is catch-up growth. And the global economy should be marked by a trend of convergence between the rich nations and the poor ones.

Obviously, this is all in theory, and in reality there are a lot of complexities—civil wars, bad governments, so on—that mean that things are quite different. But the Solow model was and is an enormously influential piece of theory. Solow won the Nobel Prize for it in 1987.

And indeed the Solow model’s prediction of catch-up growth is so influential, and so intuitive, that many people simply assume that it describes reality. Take, for instance, a recent essay by two smart people, Dwarkesh Patel and Philip Trammel. They seem to think that Solow not only described theory but also described reality: “for the past 75 years or so, the world’s poorest countries have, on average, grown more quickly than the world’s richest countries.”

But there’s a problem with that view: it’s not true.

In the 1980s, the Solow model came under attack. What changed was simply Moore’s law. Computers had become more powerful, so you could run more calculations with them. And—this was also a Moore’s Law thing, though in a more indirect way—there were now useful datasets of income for every country, like the Penn World Table. So it became possible for economists to become a lot more ambitious in their statistical work. This was the foundation of the “credibility revolution” in economics. And the Louis XVI of this credibility revolution was the idea of the Solow convergence.

Testing Solow convergence is pretty simple. You take the data from Penn and you regress income growth against initial income levels to see if poor countries were outgrowing rich ones. And whenever economists did that, they found that Solow convergence didn’t exist. Poor countries weren’t growing faster than rich ones. Over the past few decades, in fact, rich countries had been the ones growing faster. Solow convergence, one famous paper announced in the driest of academic English, was “inconsistent with the cross-country evidence.”

And then it got worse. In the 1990s the economist Angus Maddison published datasets for income going back to 1870; and in 1997 Lant Pritchett, another economist, used that data to publish a paper with regressions going back to 1870. Pritchett found that throughout the entire modern economic era, the global economy had been marked by divergence. The gap between rich countries and poor ones hadn’t been shrinking. It had been growing.

This was a big problem for economics. Solow’s growth model was a cornerstone of the field, a load-bearing theory for a lot of other things that economists wanted to keep around. And it was a real issue that one of its core predictions was getting falsified over and over.

And so economists looked for patches. Some of them opted for growth models that allowed for potential non-convergence between rich countries and poor ones. Others abandoned the “unconditional convergence” that Solow’s model seemed to imply for what they called “conditional convergence.” They adjusted for metrics like human capital or institutional quality and found that if you conditioned on those variables, if you made “all else equal,” well, then poor countries were growing faster. (Of course, “conditional convergence” was also basically meaningless, because in the real world all else was not equal. Mozambique is not Germany, and if it’s outgrowing Germany once you adjust for the ways it’s different then you’re just talking about a different country that doesn’t exist.)

And so, after all was said and done, very little was left of Solow convergence.

But then something changed.

Convergence comes alive?

In 2018, Subramanian, Sandefur, and Patel published a blog post called “Everything You Know about Cross-Country Convergence Is (Now) Wrong.” Just when economists had given up on convergence, it had come alive. “While economists were busy refining the econometric tools for studying divergence,” they wrote, “the basic facts about economic growth around the world turned completely upside down.”

As the three economists wrote:

While unconditional convergence was singularly absent in the past, there has been unconditional convergence, beginning (weakly) around 1990 and emphatically for the last two decades. … [At] the country-level at least, we should shed the idea of no convergence. It’s not “just” China and India, home to a third of the world’s population on their own: developing countries on average are outpacing the developed world.

And this wasn’t just because rich countries were growing slower. “Convergence in the recent period,” they said, “is a consequence of both improving per capita GDP growth in poor countries and declining growth in rich countries.”

They were careful to note, of course, that the pace of convergence was modest. When they published their 2021 paper to formalize their findings, they pointed out that the observed rate of growth was so slow that the average developing country would close half the gap to its potential income in about 170 years.

But it was still convergence, and that was what mattered. And so a lot of people were quick to announce the battle won. Solow convergence was back! Take Noah Smith, writing in Bloomberg about the blog post: “the implications for the world are enormous”; “ex-colonies [will] assume more global leadership”; “the world will simply be a more equal place.” Globalization had done what it was supposed to do. Economic development was working.

That celebration, it turns out, was premature. And so, only a few years after announcing the “new era of unconditional convergence,” the three economists have returned to announce that it’s over. The trend toward global convergence that began in the 1990s began to decline in the 2010s. And by the 2020s, the world had returned to a trend of divergence, with richer countries once again growing faster than poorer ones.

SS&P make two important observations about the apparent end of Solow convergence.

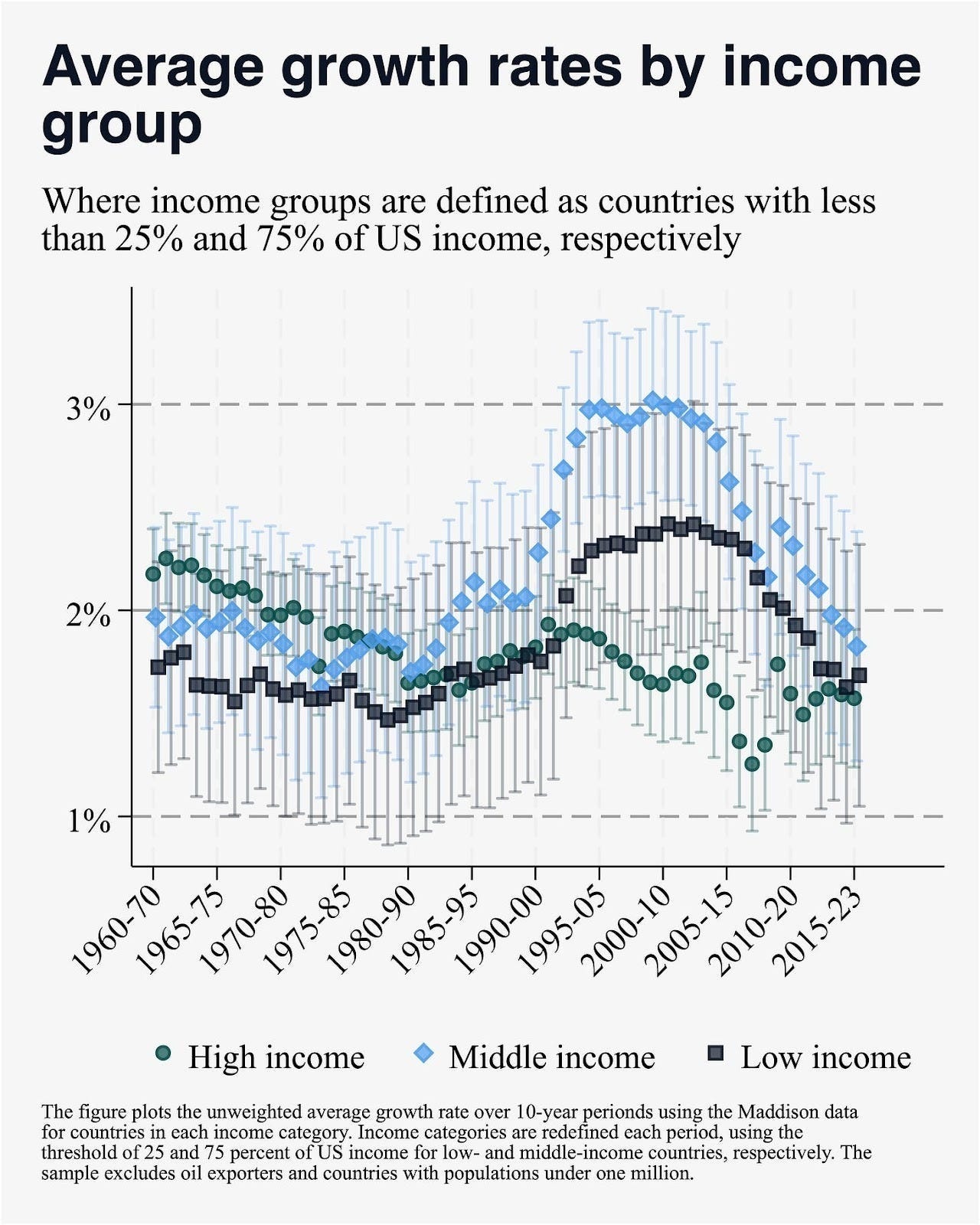

First, they say, most of the demise of Solow convergence is attributable not to rich countries growing faster, but to poor countries growing slower. It’s true that growth in rich countries is better than it was in the late 2000s or early 2010s. The dominant trend, however, is that growth in poor countries has fallen off a cliff.

And second, this collapse in poor-country growth isn’t the same across different places. Asian countries are generally doing fine. But African and Latin American countries have seen their growth rates collapse over the last 15 years. “It is slowing growth in these 2 regions that accounts for the demise of Solow convergence.”

SS&P end their essay by turning to a few potential reasons why convergence came to an end. They find a familiar culprit. Political nationalism has worsened the quality of governments around the world, they say, and new trade barriers have removed opportunities for poor countries to get richer. Neither trend looks like it will break anytime soon. So “we see little reason to hope that the world’s poorest countries will fare well in this new era of political and economic nationalism.”

Three years ago, these three economists heralded a “new era of unconditional convergence.” Now they say that convergence is over and that there’s little reason to hope that things are going to get better. That is a striking conclusion. And a grim one.

But I’m also somewhat skeptical of their account. Not their general pessimism—I agree with that part—but with the reasons they cite for why poor countries stopped growing.

What if it was just China?

I think that SS&P miss the forest for the trees. The interesting question for me is not why convergence ended, but why it happened at all. We know that in all of modern economic history, there were roughly twenty years—the period between 1995 and 2015—when poor countries were reliably growing faster than rich ones. With the benefit of hindsight, perhaps we can call it “the Great Convergence.” It was great, despite being so short, because everything else was divergence.

So what made that 1995–2015 period different? What happened between 1995 and 2015 that was so global and so important? And why did growth in poor countries collapse so rapidly in the middle years of the 2010s?

I don’t think “institutions got better, and then got worse” is a great answer. It doesn’t tell us why convergence started when it started and why it ended when it ended. There were a lot of civil wars that ended in the 1990s and 2000s, but I don’t really know if, say, Zambia was much better-governed in 2005 than it was in 1985. And then is it much worse-governed in 2025 than it was in 2005? Maybe. I don’t really know. But I just don’t think the differences in governance were big enough to explain a huge and sudden collapse in growth in the mid-2010s.

The same, by the way, with trade. Yes, rich countries—or at least America—have become more protectionist over the last few years. But there was no dramatic collapse in trade’s contribution to GDP in African and Latin American countries that would explain why growth suddenly fell apart there. Trade’s share of GDP is generally not growing as much as it used to, but it’s not a rapid contraction. Take Ghana, for instance. Trade contributes about as much to Ghanaian GDP as it did in the mid-2000s: 70 percent in 2024 against 65 percent in 2006. Ghana has not been cut off from the world economy. But income growth has still slowed dramatically. The pattern, in fact, is the same that you see elsewhere: massive growth until the mid-2010s, then a dramatic slowdown. Between 2009 and 2013, Ghana’s real per capita GDP grew by more than 30 percent; but between 2013 and 2017, it grew by just 7 percent.

So something else must have happened: both to start the Great Convergence, and to end it. The answer, I think, is China.

It’s hard to really grasp the scale of Chinese growth over the last few decades, because it’s also hard to grasp the scale of China. China is a huge country that was very poor for a long time. When it started to grow, and grow fast—remember, every industrialization is more rapid than the last one—China acted on the world economy with an unbelievable gravitational pull. My favorite figure to illustrate this: between 2010 and 2012, China consumed 40 percent more cement than the U.S. consumed in the entirety of the twentieth century.

Chinese growth, which reached its full momentum in the 2000s and early 2010s, caused the largest commodities boom in world history. It was a fantastic time to be an exporter of oil, of course, which is why countries like Venezuela or Ecuador were doing so well in the 2000s. But it was a fantastic time to be an exporter of any raw resource: copper, soybeans, aluminum, anything. And most poor countries are either exporters of raw resources or do a lot of trade with exporters of raw resources. And so between the late 1990s and the early 2010s, poor countries experienced their strongest episodes of growth ever.

Consider Brazil. Between 1980 and 1995, Brazil’s real per capita GDP grew at an average annual rate of just 0.1 percent—in other words, it barely grew at all. But the Chinese commodities boom touched off massive increases in demand for soy, iron, and oil; and so between 1995 and 2010 Brazil’s average per capita GDP growth was a solid 1.9 percent per year.

We see the same elsewhere, particularly across Latin America and Africa. SS&P try to correct for the impact of resources to GDP by excluding oil-exporting countries from their regressions. But Chinese growth touched off resource booms in every part of the poor world—in Bolivia, Paraguay, Peru, Chile, Mozambique, Ghana, Zambia, and even in badly troubled nations like the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Resource booms, though, are a kind of sugar high. They distort the economy and make it difficult to invest in non-resource sectors; and the capital accumulation they generate often isn’t useful for much outside of extracting more copper or growing more soybeans. And, worst of all, they tend to come crashing down.

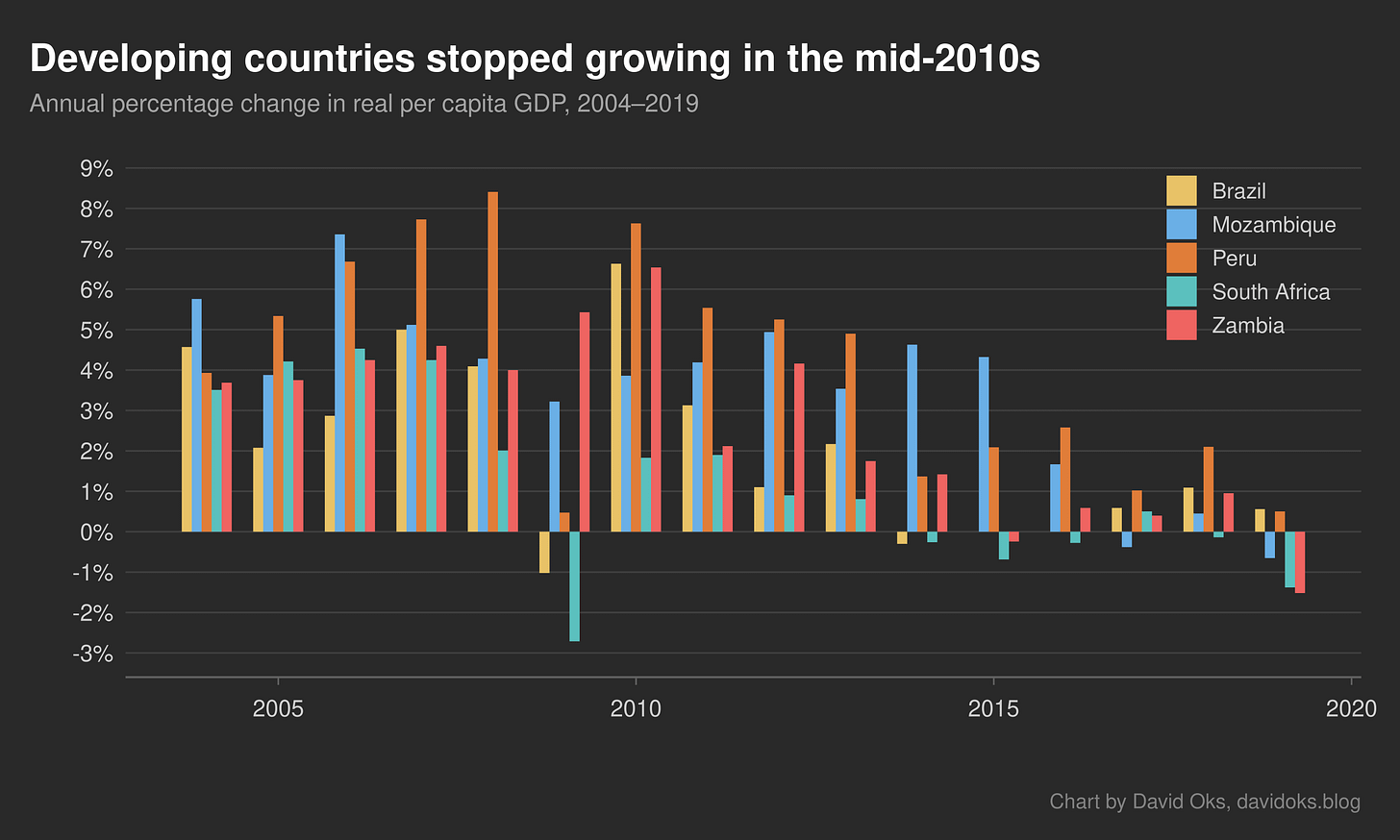

That’s exactly what happened in the mid-2010s. Chinese growth began to flag, and oil prices began to fall because American shale oil started entering global markets. And suddenly growth in poor countries collapsed. Mozambique’s per capita GDP grew at an average rate of 5.2 percent per year from 2004 to 2014; between 2014 and 2024 that fell to 0.3 percent. Zambia’s annualized growth fell from 3.5 percent to 0.3 percent. Peru fell from 4.5 percent to 1 percent. Brazil fell from 2.3 percent to 0.2 percent. South Africa fell from 2 percent to negative 0.75 percent.

And so the Great Convergence came to a sudden end. The end was so sudden because the whole thing was hollow. There was no durable process of capital accumulation or productivity growth underway in most of these places. If there had been, we wouldn’t expect the growth to stop so suddenly and then have so much trouble getting started again afterward.

Indeed, it’s not hard to conclude that the Chinese commodities boom actually weakened these countries in certain ways. Dutch disease made manufacturing in these countries less competitive; and a flood of imports from Chinese manufacturers destroyed what little manufacturing capacity they had built up. So these countries left their growth spurts with less manufacturing capacity than when they had entered it. This is the “premature deindustrialization” of poor countries that Dani Rodrik talks about.

This explanation also does a lot to explain the regional pattern that SS&P highlight. Asian countries tend to be less resource-dependent than Latin American or African ones. (Ignoring the Middle Eastern countries, which are mostly excluded from SS&P’s sample anyway.) Those Asian countries have continued to do fine. But it’s the collapse in growth among the resource-reliant countries of Africa and Latin America that ended the Great Convergence.

This leaves us with a grim conclusion. It suggests that the Great Convergence was simply the product of the Chinese commodities boom, and little more than that.

But we should give a lot of credit to Subramanian, Sandefur, and Patel for their honesty in acknowledging that the facts have changed. We can hope that, like Lant Pritchett before them, they’ll be proven wrong again by the facts on the ground. But hoping isn’t the same thing as having reason to expect it.

Great article! Do you expect that, conditioned on rapid growth in India, a similar period of growth might reoccur? I would imagine that depends on the nature of Indian growth.

Turns out merit matters more than resources.

Also does this imply that countries that specialise in low skilled manufacturing are likely to do better now that China has industrialised and getting older?