Were European immigrants to the U.S. always considered white?

No, not really

The blogger Cremieux, who mainly writes about weight loss and pharmaceuticals, posted a piece today called “European Immigrants Were Always Considered White.” I read the post on a long-haul flight from Europe to the U.S. and, though sleep-deprived, was sufficiently offended by the piece’s shoddiness that I got into an argument with the author in the comment section. He has an audience of some size, so for the sake of showing people a more intelligent way of thinking about this question I wanted to outline how exactly he goes wrong.

The core of the piece is this: Cremieux claims that the idea that immigrants from southern and eastern Europe were historically considered something other than white and eventually “became” white in one way or another—this is the narrative you see in books like Noel Ignatiev’s How the Irish Became White, Matthew Frye Jacobson’s Whiteness of a Different Color, and David Roediger’s Working Toward Whiteness—is an academic myth. Instead, he argues, Irish, Italians, Jews, and Slavs—the groups I’ll hereafter just call “the ethnics” as a shorthand—were always considered white. In his words, “the notion of a constructed White race that different groups have been given entry to is just a divisive academic device lazily conflated with the commonsensical perception of people being White.” (An aside: the tendency to capitalize the words “white” and “black” is one of the more irksome language trends of the last few years. I wish we would go back to 2019.) He argues that these groups are visibly white, were legally classed as white, and simply were always white.

In defense of this proposition he cites a few things:

There were no laws banning marriage between ethnics and “Old Stock” whites, as there were for whites and blacks and occasionally whites and other non-white groups (such as Chinese or Filipinos): “miscegenation laws never considered European immigrants to be non-White.”

There was no legal architecture separating ethnics from the category of whiteness: “U.S. military forces were segregated into ‘white’ versus ‘colored’ units, and European immigrants always fell on the White side of that divide”; similarly, people from anywhere in Europe were always eligible for naturalization as citizens under the 1790 statute that limited citizenship to “free white persons.”

Rates of lynching show that ethnics were targeted at a rate closer to “Old Stock” whites than to blacks: “there was no sustained regime of lynchings aimed at Europeans as a racial class.”

I should distinguish here between two versions of the argument that Cremieux is making. The weak version of his argument is simply that under U.S. law immigrants from southern and eastern Europe were generally considered white. The strong version is that in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries immigrants from southern and eastern Europe were socially accepted as white in American society.

The weak version is mostly true but also trivial: no one has ever denied that in the nineteenth century Italians and Irish were allowed to naturalize as citizens and that there was no system of Jim Crow based around the subjugation of, say, the Poles and Slovaks. Legally speaking, all of these European groups were classified as white, and while the U.S. government clearly preferred some whites over others—thus the 1924 immigration law that sharply restricted migration from southern and eastern Europe but not from northwestern Europe—it never enforced a statute distinguishing between the racial character of Italians, Irish, and Jews and that of Old Stock whites.

Meanwhile, the strong version of Cremieux’s claim—the argument that ethnics actually had a racial status akin to Old Stock whites in American society—is stupid and historically illiterate. Unfortunately, judging by the his comments in the piece, Cremieux is more interested in the strong and stupid version of the claim.

As I wrote above, it is true that in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries ethnics had the same legal rights as Old Stock whites and had the legal status of being “white.” But the legal status of “white” did not mean that someone was actually seen as white. For most of the nineteenth century “white” as a legal status just meant “neither black nor Indian,” and since Indians were an ever-diminishing presence in national life being white essentially meant that you weren’t black (or, after 1870 or so, Chinese).

Thus the Siamese twins Chang and Eng Bunker, though never considered quite “white” by others, could naturalize as U.S. citizens at a time when it was restricted to “free white persons,” could marry white women, and could list themselves as “white” on the Census even once “Chinese” was an available category; and Mexican-Americans, no matter how swarthy they might be, were effectively granted the legal status of “white” by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, with that status affirmed in In re Ricardo Rodríguez in 1897 when an illiterate Mexican man (the aforementioned Ricardo Rodríguez) was naturalized as a citizen even when naturalization was limited to whites and blacks. Neither the Bunkers nor Rodríguez were socially considered white, but they were still able to attain the legal status of “white,” because that legal status was not the same thing as the social status of being considered white by others.

In short: “white” was a legal category. It was not an attempt to define a “white race,” because no one considered Chang and Eng Bunker or Ricardo Rodríguez to actually be white. It was not until the period after the civil rights revolution of the 1960s that bureaucrats started to think seriously about having government racial categories correspond to something like “the races of the world.”

So the people who fell under the “white” legal category were not necessarily treated as white socially. To take the first argument that Cremieux cites: it is true that no miscegenation laws prevented the marriage of ethnics and Old Stock whites; but he forgets to point out that in many states there were also no laws banning the marriage of whites and blacks. That does not tell us that in those places intermarriage between whites and blacks was common or acceptable: even where intermarriage was legal, the marriage of whites and blacks was exceptionally rare and socially verboten. The same was true for the intermarriage of ethnics and Old Stock whites until well into the twentieth century. It may have been legal for an Italian or Jew to marry an Old Stock white but it was exceptionally uncommon; and where it did occur it was a cause of local scandal and ostracism.

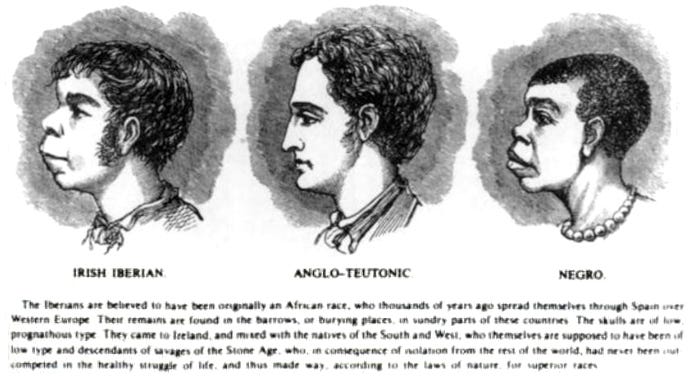

So the ethnics weren’t on the level of blacks, but neither were they quite like the whites. They were, as Roediger says, “inbetween peoples,” occupying a place in the racial hierarchy somewhere lower than Old Stock whites and higher than blacks. Practically nothing about the ethnic experience in America tells us that they were considered “white” in anything but the legal sense. They lived in enclaves that were extremely spatially segregated from the settlements of the Old Stock whites and remained so well into the twentieth century. From public culture as well it is obvious they were not seen as fully white. Until 1880 one could find in minstrel shows the Irish-American stock characters of “Pat” and “Bridget” alongside Jim Crow and “Dandy Jim from Caroline”; Irish laborers were seen as so contemptible that slaves would joke that “my master is a great tyrant, he treats me like a common Irishman”; as late as 1899 the hugely popular Harper’s Weekly published illustrations showing the “Irish Iberian” skull to be more similar to that of the “Negro” than to that of an upright “Anglo-Teutonic” gentleman. It’s obvious that the ethnics were not simply considered white.

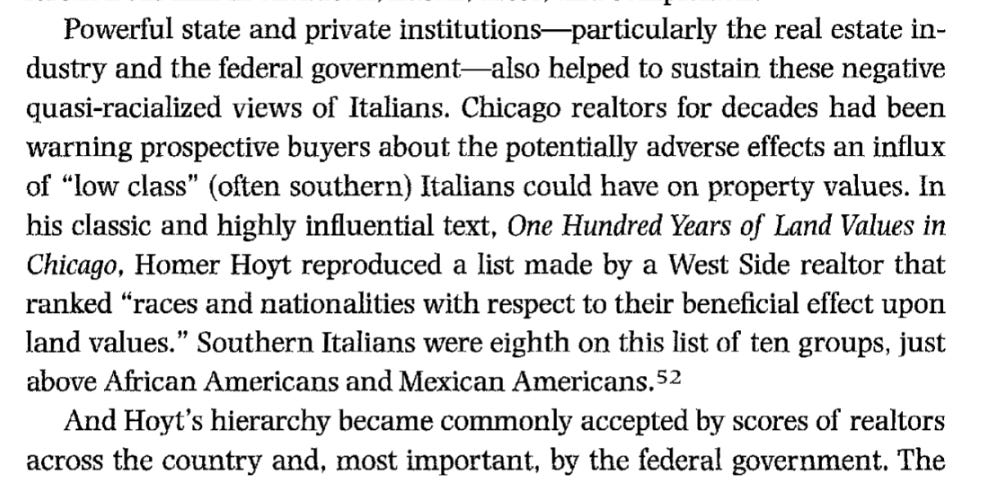

It could be that these comparisons were just terms of abuse. But the weight of the evidence clearly indicates that these groups were widely viewed as occupying a place in the racial hierarchy below true whites and above blacks. Thomas Guglielmo, the same author that Cremieux cites to show how Italians were “consistently and unambiguously” placed on the side of whites compared to blacks, writes later in the same book about how Italians were ranked only above blacks and Mexicans in their “beneficial effect upon land values.”

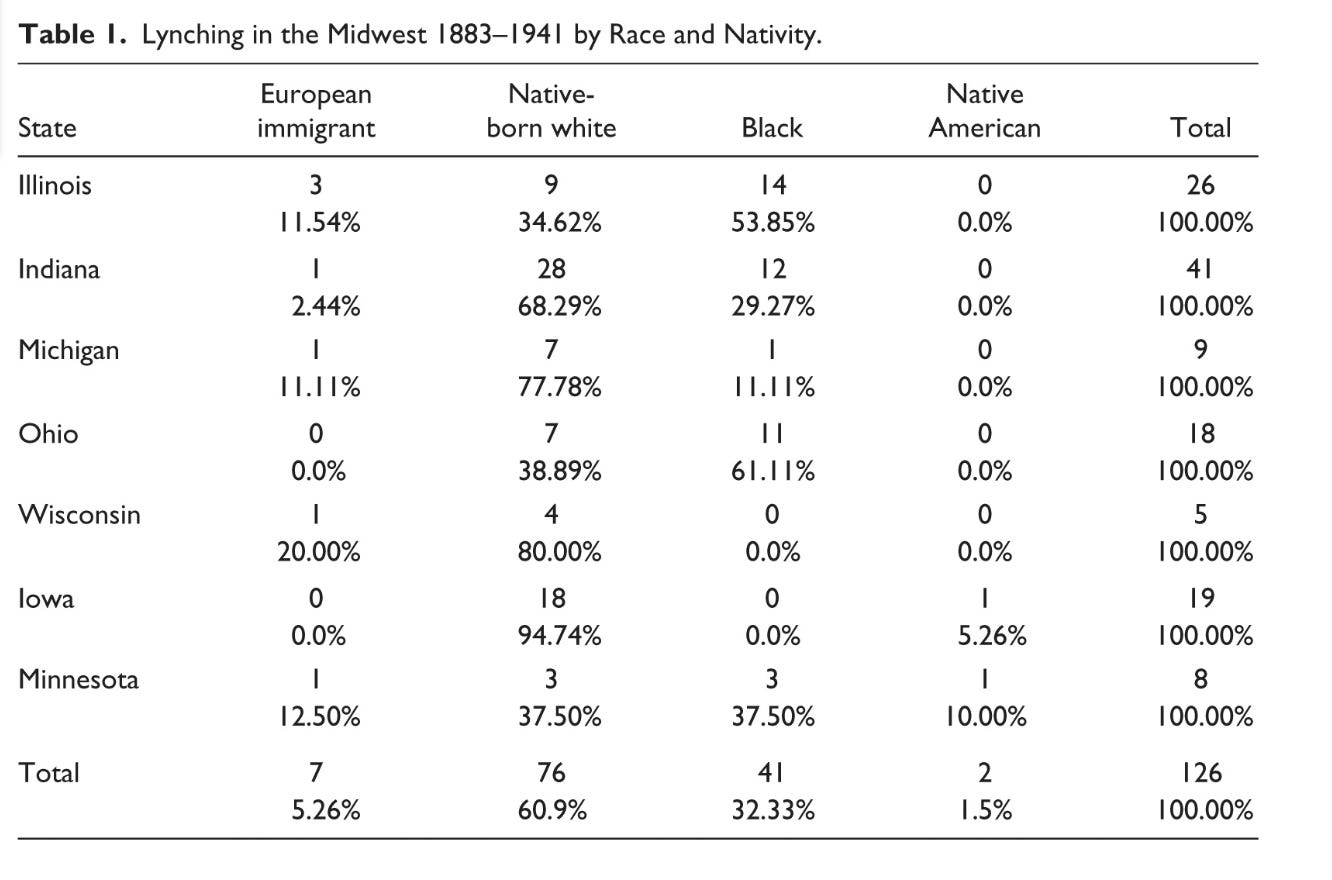

I should conclude with the last piece of evidence that Cremieux cites in favor of his argument that southern and eastern European migrants were considered white, because it is so unusual and poorly constructed. He cites lynchings, which he calls “a true test of group identification by way of serious extrajudicial and extralegal violence,” and uses a dataset from the Tuskegee Institute of all the lynchings carried out in the United States from 1882 to 1968. Of all the lynchings carried out during this period, about 70 percent were carried out in former slave states against black people; another 15 percent were carried out in those same states against white people; and most of the remainder were carried out in the semi-governed states of the far west.

Cremieux wants to prove that there was no significant difference in the rate of victimization by lynching between ethnics and Old Stock whites. To do this he cites a study looking not at the South or the West but at the states of the Midwest—the only region where white victims could be disaggregated by their ethnic background—and which finds no real difference in rates of targeting between ethnics and Old Stock whites. But over the 58 years that the study inspects there were a total of 83 lynchings of white people across seven large states—Iowa, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio—leading to about 1.4 lynchings per year across the entirety of the Midwest. Why one should extrapolate much of anything from an event of such low frequency is unclear; why one should extrapolate the racial position of ethnic whites in particular from lynching rates is particularly puzzling, given that only seven ethnics were killed during the entire period surveyed.

None of the arguments I’ve made above are particularly innovative or controversial. One doesn’t need to endorse all the claims advanced by Ignatiev, Roediger, and Jacobson—I personally don’t think that the assimilation of these ethnicities into mainstream white culture had much to do with their adopting racism against blacks, for instance—to recognize that the historical record strongly shows that in the nineteenth and early twentieth century immigrant ethnics were not socially accepted as fully white, whatever their legal status.

Are current immigrants to the west going to assimilate the way the Irish and Italians did?

That’s the basic question at hand with the meaningful current policy choice.

The answer is no. The Irish and Italians assimilated because they are white. While they had differences with old stock whites, these are small compared to the differences between whites and non whites.

People trying to use the experience of white ethnic immigration pre 24 to justify current non-white immigration are simply incorrect.