Southern Italy is poor because of malaria

A plasmodial theory of divergent development

A few days ago someone named Michael Arouet went viral on Twitter with this post:

I have never understood the massive economic divide in Italy.

Why is the North with its various industries one of the wealthiest areas in Europe, but the South so extremely poor? Same country, same language, same laws and taxes. Can someone please explain?

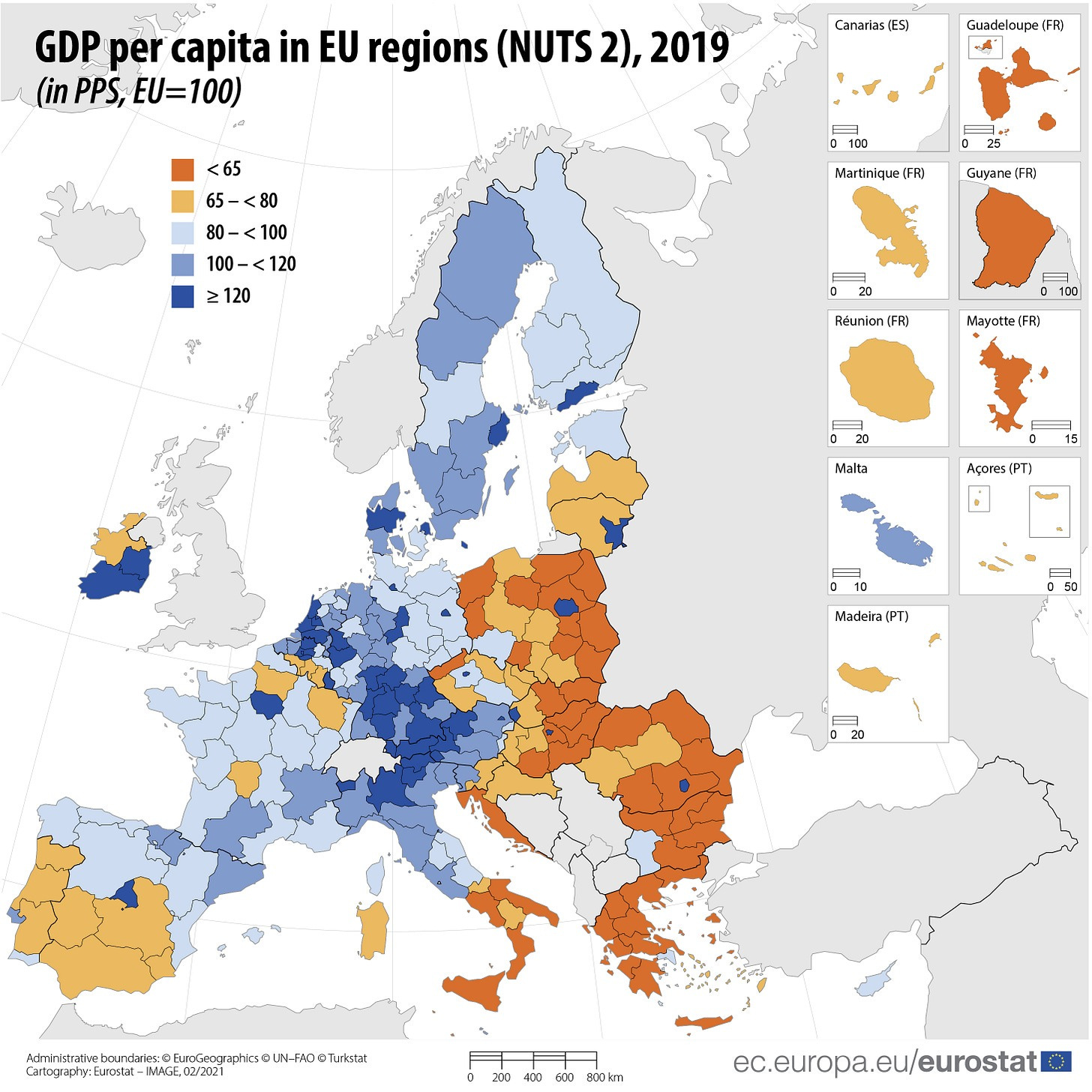

I’m glad that Michael’s tweet went viral, because it’s a very interesting question. Italy is an extremely unequal country: the gap between northern Italy and southern Italy is much wider than the Westen/Osten divide in Germany or the north/south divide in the United Kingdom. Northern Italy is comparable in wealth to such beacons of Mitteleuropa prosperity as Austria and southern Germany; southern Italian states like Calabria and Sicily, meanwhile, are some of the poorest parts of the European Union, with per capita incomes on par with Romania and Bulgaria.

This gap has been present for a long time. When Italy was unified, it was obvious to most involved that northern Italy and southern Italy, the region called the Mezzogiorno, were basically different countries: thus Massimo d’Azeglio’s famous line that “we have made Italy; now we must make Italians.” (Sicilian and Piedmontese, it should be remembered, were not mutually intelligible.) In the years after unification this “Southern question” (the questione meridionale) became one of the dominant issues of Italian political life. That gap has remained pronounced in the century-and-a-half since unification—enough that there have been prominent separatist movements in both the south and the north of Italy—and so the Southern question has remained a long-running matter of contention within Italy, with an area of study, meridionalism, even spawning to study the issue.

Unfortunately this long tradition of trying to study the divergent trajectories of north and south Italy did not do much to improve the caliber of answers to Michael’s question. I won’t go individually through the answers, except to note that most of them just beg the question. Yes, southern Italy has institutions and cultural norms that seem to be less conducive to development; but the interesting question is why it has those institutions and northern Italy does not.

So I will do Michael a favor and provide an answer. South Italy is poorer than the north because of malaria, and what malaria did to the patterns of landowning and agrarian life, and what the patterns of landowning and agrarian life did to human capital and social trust.

South Italy’s geography caused malaria…

We should start with a few words about the disease that humans call malaria: malaria having its origin in the medieval Italian for “bad air.” We now know that malaria, perhaps the deadliest disease in the history of our species, is caused not by “bad air” but by protozoan parasites of the genus Plasmodium, which are transmitted into the bloodstream of primates, birds, and reptiles by mosquitos of the genus Anopheles. These mosquitos breed in still bodies of water, and thus tend to be prevalent in areas dominated by marshes or shallow pools; and because the developmental lifecycle of Plasmodium is aided by heat—the hotter the climate the faster they develop—one tends to encounter malaria most densely in areas that are hot and wet.

There are a few malarial areas in the north of Italy, though those places are generally cold enough that the strand of Plasmodium that could survive there is the relatively mild Plasmodium vivax, which is not so grave a threat to humans. In the central west of the Italian peninsula, by contrast, you have notoriously pestilential marshlands like the Pontine Marshes, which Julius Caesar had wanted drained before his assassination; there were various unsuccessful attempts in the 2,000 years that followed until Mussolini finally succeeded in draining them via massive mechanical pumps in the 1930s. Throughout the south, meanwhile, malaria was widespread due to river conditions: whereas in the north the Po River was fed by meltwater from the Cottian Alps, the Apennines that dominate the topography of the south aren’t tall enough for year-round snow; and so southern rivers are fed exclusively by the rain, and thus flood in the winter and dry up in the summer—in both seasons leaving behind endless puddles. It was, in short, an ideal environment for Plasmodium falciparum, the parasite that causes the deadliest form of malaria.

P. falciparum first came to Italy sometime around 500 BC, likely coming up through north Africa; we can track its arrival by the abandonment of settlements in areas that were gradually made uninhabitable by endemic malaria, such as the Greek city of Paestum in what is now Salerno. By 100 BC malaria had become widespread throughout the south of Italy and the western coast.

…malaria caused latifundism…

Before P. falciparum arrived, these regions of Italy had been dotted with small farms. But as malaria became endemic that way of life collapsed. Because the disease peaks in summer and autumn, labor-intensive, year-round crops like wine grapes and spring-sown wheat cannot be harvested except at grave personal risk; and so smallholders, unable to forgo two critical growing seasons, abandoned these regions en masse, typically for agricultural colonies elsewhere in the Roman world. As they left, their small farms were gradually replaced by massive latifundia, and free labor was replaced by chattel slaves imported from conquered regions. From one account of this process:

The reason for the genesis of an economy based on mass chattel slavery in western central Italy (and large parts of the south of Italy) in antiquity is fundamentally exactly the same as the reason why it arose in the western hemisphere after Columbus. A spreading disease (in this case P. falciparum malaria) gradually, by a slow process of attrition, either killed or forced to emigrate the bulk of the indigenous farming population in Latium and southern Etruria, thus providing the manpower for Roman colonization elsewhere. That, in turn, created a vacuum, a massive labour shortage, on fertile agricultural land where free men were reluctant to work because of the disease. That labour shortage could only be filled by importing large numbers of chattel slaves. … Their owners need not worry if the gangs of slaves employed on the land … suffered extremely high mortality rates from malaria; slaves were very cheap and easy to replace.

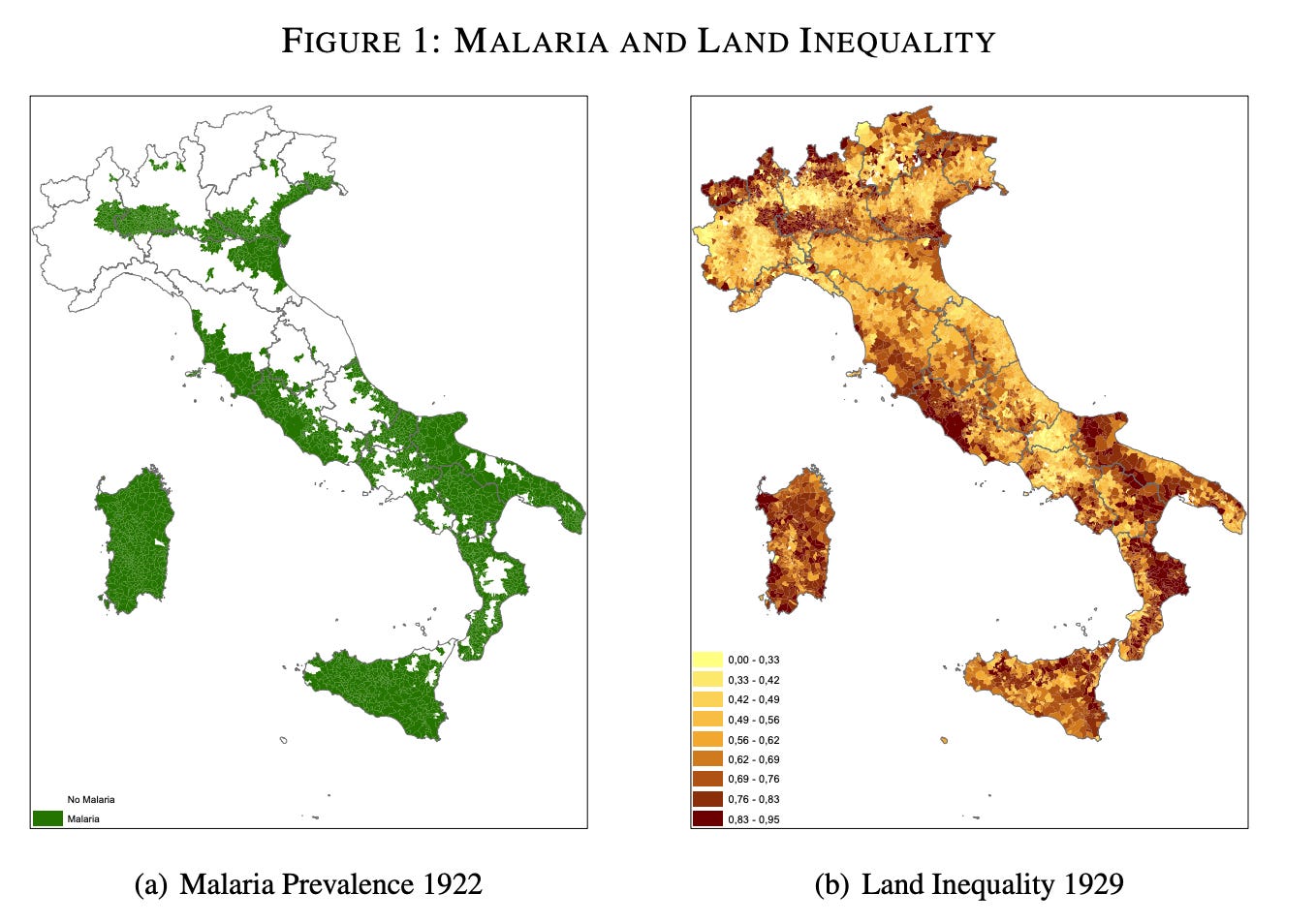

As that excerpt notes, this was not unique to western central or southern Italy. Wherever malaria has coexisted with pastoral agriculture—in the American South, the Caribbean islands, Brazil, in the Arabian peninsula—it has tended to select for large estates manned by slaves. Thus we see, in the case of Italy, that malaria prevalence was strongly correlated with land inequality.

Malaria remained endemic in southern and central western Italy for the following two millennia; it should not be surprising that the same basic pattern of landownership persisted along with it. In northern Italy one could find freer forms of labor, like the commercial farming of the Po Valley or the mezzadria system of Tuscany where farmers and landlords split produce and profits equally; but in the south the chattel slavery of the Roman world gradually evolved into a system of severe debt peonage that closely approximated slavery. In the latifondi the authority of the landlords was absolute. Every empire that held sway over southern Italy, from the Arabs to the Spanish, merely served to ratify the rule of the landlords. (The sole exception is when Napoleon, having conquered Italy, sought to abolish the institutions of feudalism; but the landlords quickly regained control over their possessions, now classified as private property rather than feudal inheritance.) It is a common mistake to think, particularly in premodern conditions, that because a given empire controls a territory it actually administers it: in southern Italy it was the landlords who exercised the law and held effective control over the region. Peasants, utterly landless, lived in hillside “agro-towns” to avoid the malarial lowlands; each day they traveled into the fields to work, with their labor overseen by the landlords’ overseers and enforcers. It was a far more severe system of exploitation than the land tenure regimes that emerged elsewhere in Italy.

…and latifundism caused a lot of bad things…

The latifondi system had three consequences worth highlighting. The first is that southern Italian peasants had stronger kinship ties than peasants elsewhere in Europe. In most of western Europe, kinship groups were gradually broken by the interventions of state and religious authorities, for whom strong clan ties were a threat to the stability of both the feudal system and the authority of the Church; the most famous facet of this process was the prohibition on cousin marriage, explored by Joseph Henrich and others. But in southern Italy absentee landlords had little interest in regulating the lives of the landless peasants in the agro-towns: they did not bother with dismantling the clans and extended family networks that characterized southern Italian peasant life, either because they were disinterested—very few of them lived on the land because the land was malarial, after all—or because their power was so absolute that clans among the peasants did not threaten them. Thus we see throughout southern Italy all the marks of strong kinship ties: higher rates of cousin marriage, a greater prevalence of destructive family feuds (thus the term vendetta), and the family structure that undergirded such clan-based organized crime formations as the Sicilian Mafia, the Calabrian ‘Ndrangheta, and the Neapolitan Camorra. More generally, we see the type of “amoral familism” that the sociologist Edward Banfield associated with southern Italian life in his famous study The Moral Basis of a Backward Society: an ethic that sought to “maximize the material short-run advantage of the nuclear family, and assume that all others will do likewise,” and which he attributed to the high rates of death and defective system of landownership he saw in southern Italy.

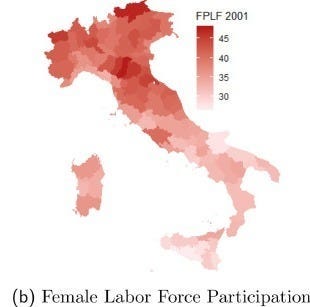

The second inheritance of the latifondi is the low status of women throughout southern Italian society. Whereas on northern Italian farms women might tend kitchen gardens or raise poultry, in the south they were generally excluded from agricultural work—which was, after all, much more dangerous than in the north—and confined to the management of domestic activities, such as weaving and bread-making. This division of labor informed the strongly patriarchal cultural norms characteristic of southern Italy, whose imprint one can still see in maps of female labor force participation in the 21st century.

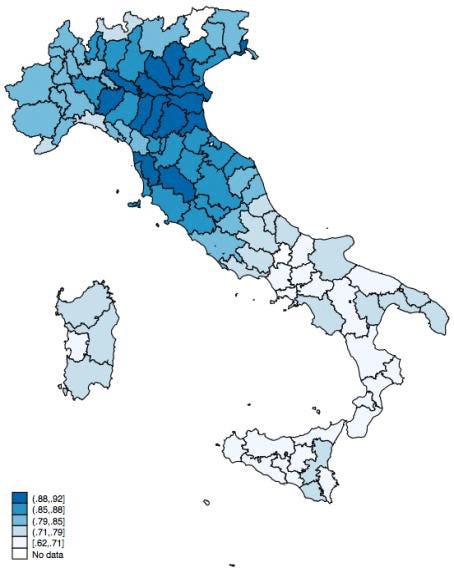

The third inheritance of the latifondi is the remarkably low level of human capital accumulation in southern Italy. As in other places characterized by the political and social dominance of extractive landowners, such as in Latin America, landed elites were generally antagonistic to mass education for the peasants, for the simple reason that there was no benefit to be gained from smarter farm laborers. Thus we see the same pattern of malaria and land inequality repeated in a map of literacy rates from 1929.

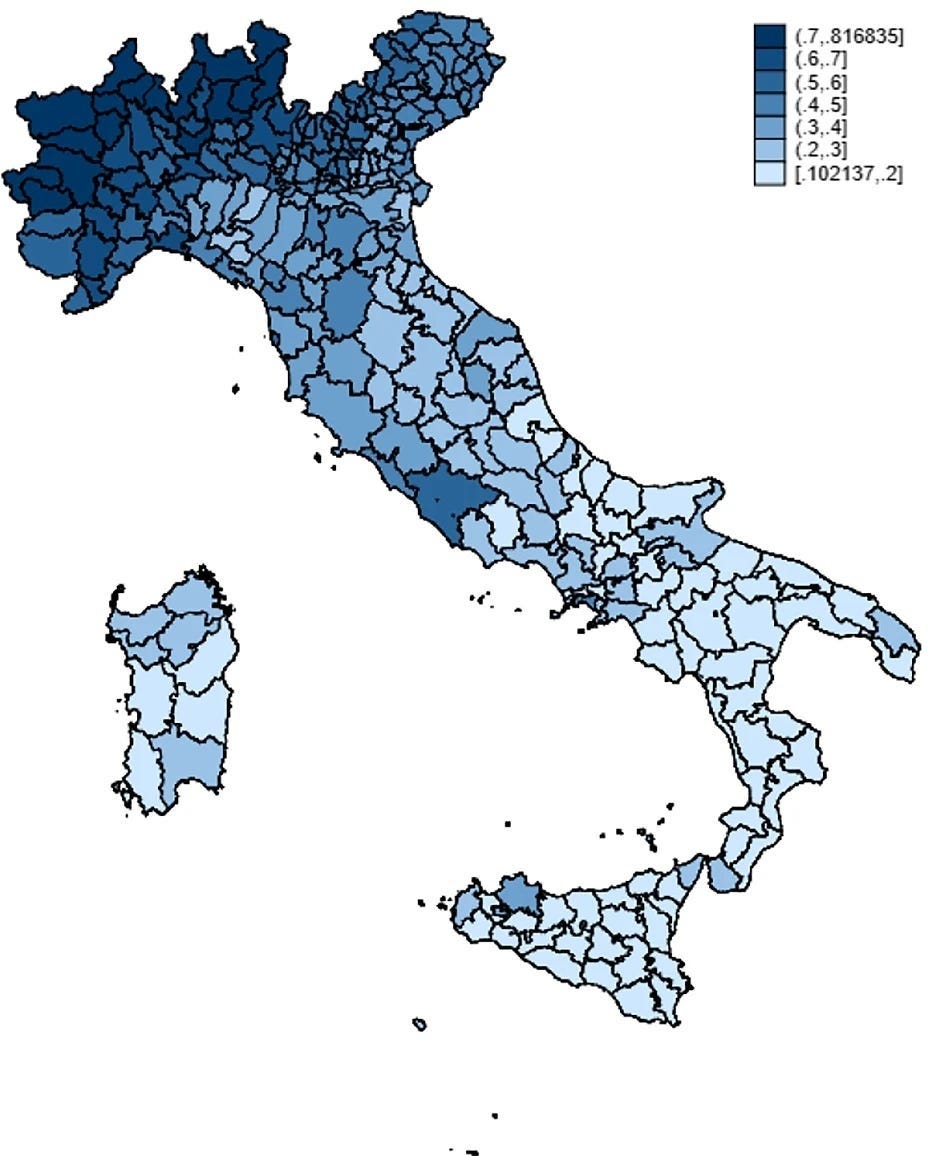

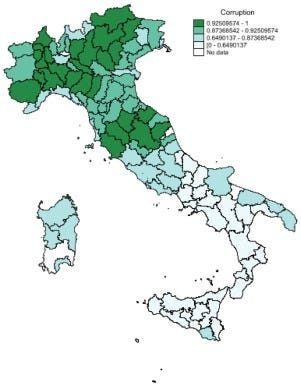

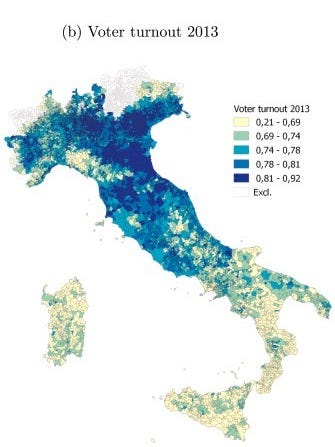

Out of these features of southern Italian society sprung many of the pathologies that plagued southern Italy throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: the ubiquitous brigandism and banditry, the enduring strength of organized crime, the widespread sense of civic apathy, and the “praetorian” (to borrow Samuel Huntington’s term) nature of the southern Italian political sphere, where even into the 1990s violence against public officials was an ever-present fact of life. Even today we see the same basic malarial pattern imprinted on regional maps of Italy. For instance, the strength of the Mafia and Mafia-type groups:

The prevalence of corruption:

Voter turnout:

Or even something as mundane as blood donations per capita, favored by Joseph Henrich as a proxy for impersonal social trust:

…that prevented industrialization

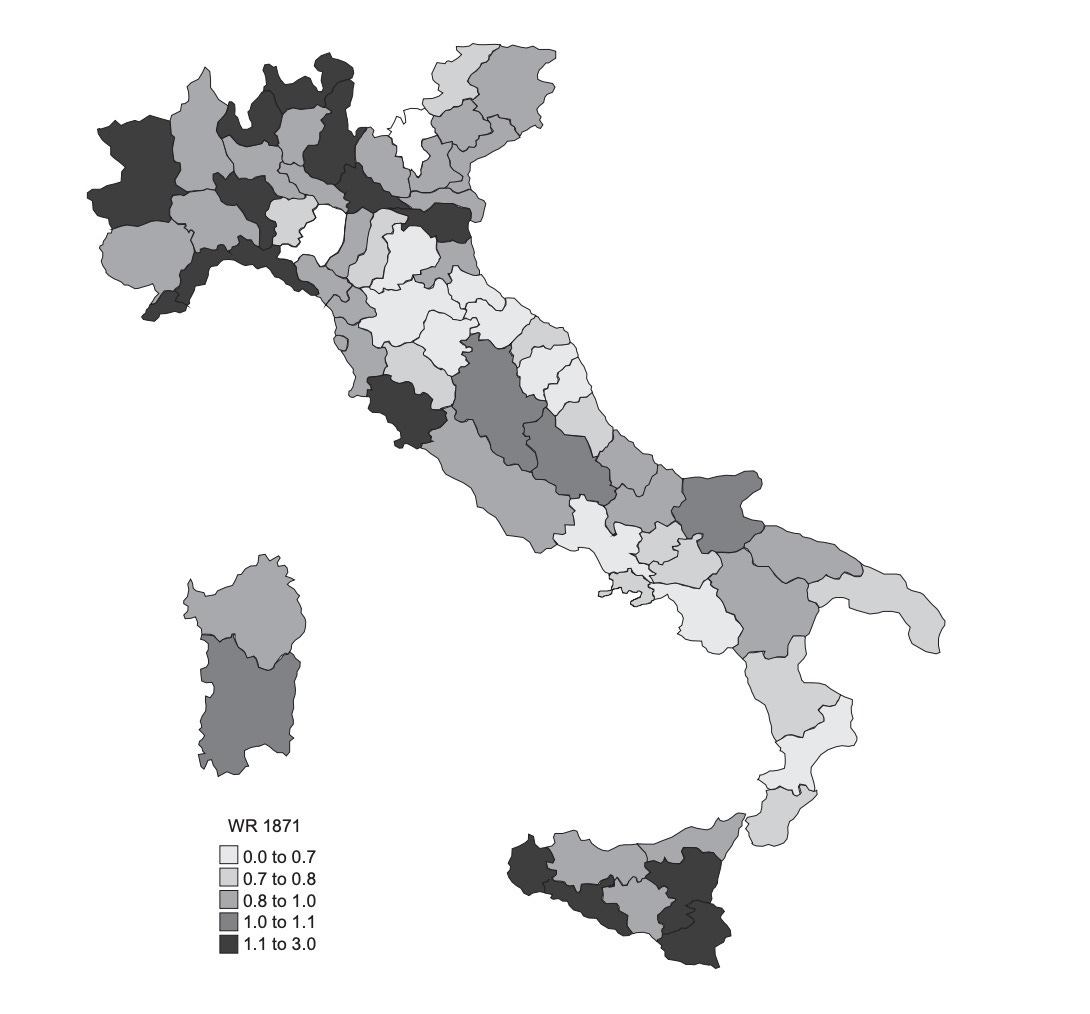

For all the social harm they did, it should be said that the latifond did not directly impoverish southern Italy. When Italy became independent, the economic gap between north and south was not enormous; in 1871, ten years after unification, northern Italy was only somewhat richer than the south in terms of real wages, and there were several parts of the south that were richer than parts of the north. Both north and south were predominantly agrarian; and so its human capital advantage could have only a limited impact on economic output.

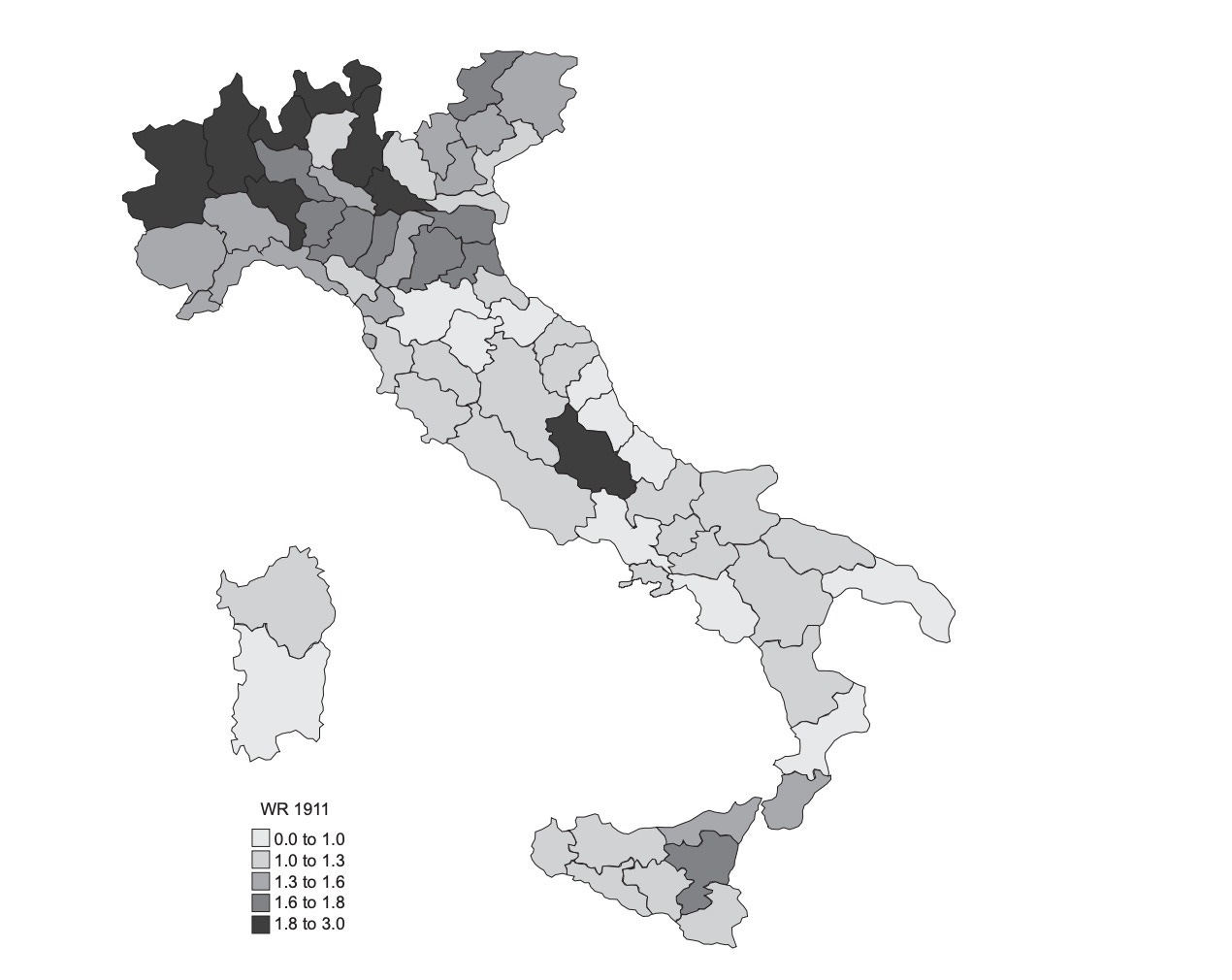

It is only in the decades after unification, as northern Italy began to urbanize and industrialize, that the human capital gap between north and south began to matter tremendously. By 1911 a clear north-south gradient in real wages had emerged.

The most important long-term effect of the latifondi, then, was social and cultural. Northern Italy had developed a relatively educated and skilled workforce, networks of commercial trust, and something of a developmental coalition among its elite, who were predominantly mercantile and industrial rather than agricultural. Thus northern Italy was able to absorb workers from the countryside into the factories and industrialize quite rapidly, and a few decades into the twentieth century it had converged on western and central European standards of living. In the south, meanwhile, the latifondi produced an uneducated peasantry, weak horizontal ties outside the family, and a predatory elite whose wealth came from extraction rather than investment. It thus always lacked the political economy required for industrialization.

So to return to Michael’s question: yes, northern and southern Italy today share the same country, language, laws, and taxes. But they do not share the same history. For two millennia southern Italy was shaped by P. falciparum, which made smallholder farming untenable and produced a system of absentee landlordism and bonded labor, which created a society defined by weak human capital, strong kinship ties, and low social trust outside those kinship networks. Malaria was eradicated from Italy in the middle decades of the twentieth century, and in 1971 the country was declared free of the disease; and in the decades after the Second World War the country was freed also of the latifondi, which had died with malaria just as they had been born by it. But just as one can still see in the faded walls that once girdled the empire of Hadrian the outer edges of the once-great empire of the Romans, one can still spot—in maps of corruption, violence, trust, all the other sad indicators of dysfunction—the faded borders of the mosquito’s dominion. In the words of Francesco Saverio Nitti, prime minister of Italy for one year and a famous student of the Southern question:

Malaria is the basis of all social life. It determines relations of production and the distribution of wealth. Malaria lies at the root of the most important demographic and economic facts. The distribution of property, the prevailing crop systems, and patterns of settlement are under the influence of this one powerful cause.

Why were the North's elite "predominantly mercantile and industrial rather than agricultural" and is it tied to malaria in some way I didn't catch?

This is describing a mechanism to explain why that was