Social media is a demonic force in the world

Thoughts on recent events

The best thing that can be said about the death of Charlie Kirk is that it was quick. One supposes that he knew what was happening for only a moment or two and that death came to him speedily and without undue hesitation and that by the time he began to grasp what had occurred his life had already begun to take its leave of him. One supposes too that among divine mercies one could count a brief span between the moment at which one realizes that death is imminent—the confusion, the shock, the instant of searing pain, the forceful thrust of the body as flesh is ripped from its frame—and the actual moment of death, the great coldness of oblivion.

What I found most remarkable about the death of Charlie Kirk was not the specific circumstances of his murder but the way in which his death was experienced as an event online. Kirk was not the most famous conservative commentator in the United States—probably that distinction belongs to Tucker Carlson or Ben Shapiro—but he was sufficiently famous that many in the United States were familiar with his work, or more specifically with videos of him debating college students; and because he was a familiar face, particularly on the internet where those videos of him debating college students lived, the murder of Charlie Kirk was one of those sudden occurrences that caused a flood of online activity. Twitter, now called “X,” experienced its most active day in years, presumably since it was the only place in which one could find an uncensored video of Kirk being shot in the neck and dying. The video—essentially an impromptu snuff film—was shared incessantly, replayed, remixed, dissected. Everyone felt the need to say something no matter how inane or tasteless. Elon Musk said, “The shot looked real bad, but I sure hope Charlie makes it somehow.” The Republican congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene, whom one imagines would have been a friend of Charlie Kirk or at least an ally, shared a video of his murder with a bland statement of concern. Isn’t it at least in bad taste to share a video of your friend’s gruesome death? But, one could say, it was educational: the world needed to know the truth. In service of the truth commentators drew arrows to track the direction of the bullet as it pierced Charlie Kirk’s skin and made its way, in a fraction of a second, through his throat. In the service of the truth they speculated about the dying man’s odds of survival. In the service of the truth they shared and reshared the video of Charlie Kirk dying: a video so visceral and overwhelming as to be almost pornographic. The truth—this is what the world is like, don’t turn away—is a powerful defense. If the evil is real, why not know it, and make it easier to shun it? A statement many would make in defense of posting the snuff film of Charlie Kirk’s death; also the words, in Milton’s Paradise Lost, of the serpent to Eve.

First there were the expressions of horror at the event that did not impede people from sharing the video of Charlie Kirk being murdered and then the inevitable pointless controversy. The menacing statements about vengeance for his murder, skulls crushed on the pavement, traitors to the homeland prosecuted, arrested, savagely punished; then, on the platforms friendlier to the murdered man’s political opponents, a flood of comments reminding readers that however unfortunate it might be that this man’s throat had burst open in front of a crowd of his supporters and that the snuff film of his murder was being shared endlessly on social media—he had a family, after all, this was a man of flesh and blood like you and me—the dead man had made statements that might classify him as a “fascist,” or a “Christian nationalist,” or a “white nationalist,” or something along those sinister lines, and thus while he didn’t necessarily deserve it—or maybe he did, who’s to say—he was no angel. From the tension between these two poles came the inevitable recriminations, a few firings for insensitive comments, pointless bickering, oaths of eternal enmity, “discourse” about the murder, the legacy of the victim, the reaction to the murder, the reaction to the reaction to the murder, how one commentator is insufficiently kind to the memory of the dead and another commentator far too kind. Meanwhile the videos of the bullet ripping through the man’s flesh are spliced, recut, reposted, critiqued, mocked; within a few days they have been shared so extensively that they have become just another jumble of pixels and noise, one meaningless snuff film among many: the week before there had been the snuff film of a schizophrenic man stabbing a woman to death on a bus, and not long after Charlie Kirk’s death there came a video of a man in Dallas beheading the manager of the motel at which he worked. It is to our credit that we are not yet barbaric enough that we can watch a man die in front of us and feel nothing; but we have received enough training from the media—from zombie films, action movies, torture porn, videos of bleeding toddlers in war zones, livestreams of mass shootings in New Zealand—that once captured on video and converted to a stream of pixels and audio the suffering and death of others, the screams of shock and pain, the loss of bodily control, the animal whimpering of a being that is wounded past the point of return—all of this does not bother us so much.

Emmanuel Levinas, one of the finest philosophers of the twentieth century, proposed that all ethics emerges from encountering the face. When we meet a stranger we see their face, and “the skin of the face is at its most naked and defenseless,” “the most naked even though this nudity is decent.” When we encounter this face we see its weakness and vulnerability and we see also the hint of the sublime, the infinite—the world without end that resides in the person of the stranger as it resides in our own person. “The total nudity of his defenseless eyes,” then, is a plea for infinite mercy, for compassion; for Levinas it is the physical form of the most basic of all social laws, “thou shalt not kill.” But online there are no faces. The “face-to-face” that for Levinas underpins all human sociality has vanished. There are images of faces, videos of faces, things that move like humans and yet seem distant and unlike us: haunted marionettes, disembodied representations. The things you see on your screen are not real people, they are but one part of a vast and endless stream of pixels and audio; when you look away they are gone. What does it mean for social existence that our public square unfolds without seeing the faces of our interlocutors? What does that do to us?

Why was no attempt made to restrict the spread of the video of Charlie Kirk being murdered? I suppose that X is committed to the principle of “free speech.” But free speech is not a moral principle. In any human community that embraces among its tenets the notion of “free speech,” the legal reality of free speech coexists with the social reality of judgement and sanction. It is legal for me to find a snuff film of a man getting killed by a lawnmower and share that snuff film with my horrified neighbors; but freedom of speech does not mean that my doing so is virtuous because my neighbors need to learn about lawnmower safety, or that my neighbors would be in the wrong to ostracize me for sharing it, or that my doing so is in some way respectable because it is “free speech.” Speech that is legally free is thus restrained within the outer boundaries of social decorum. But online—where nobody needs to know my true name, where like a band of drifters we exist in relation to each other in states of blindness and anonymity, where we evaluate social success on the basis of engagement metrics—there is no social sanction for sharing or consuming a snuff film. In this unrestrained social world we find ourselves enamored with dismal provocation for the sake of provocation: and in this bargain we lose some noble part of ourselves, we become something our greater selves would hardly recognize. Put aside for a moment that you have a duty to other people in all their weakness and shame and stupidity. What does watching a snuff film do to your own soul?

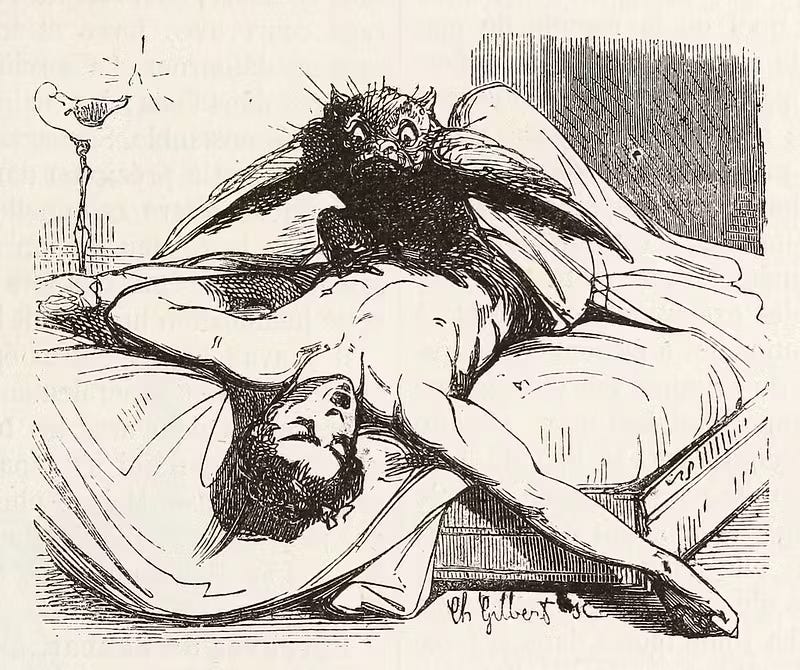

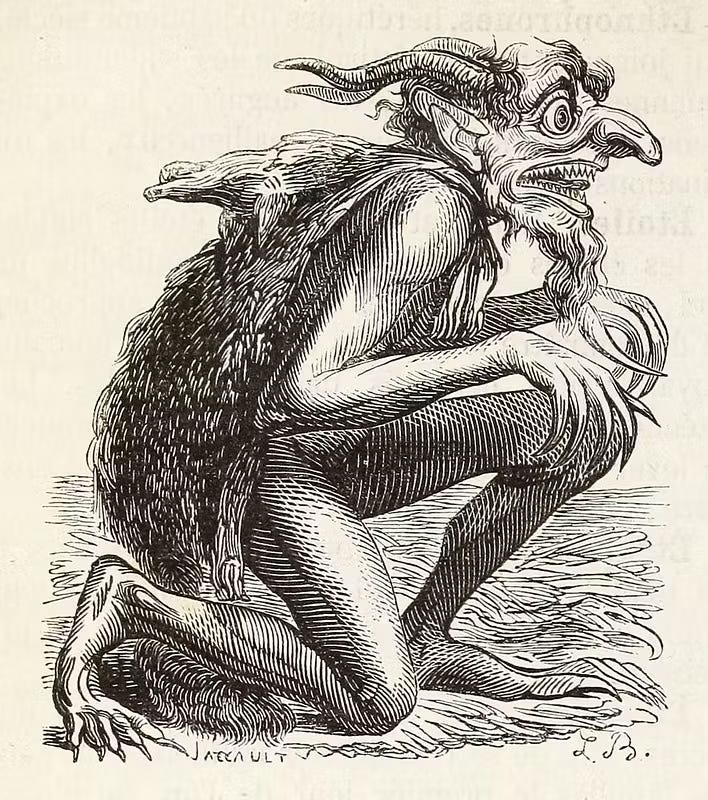

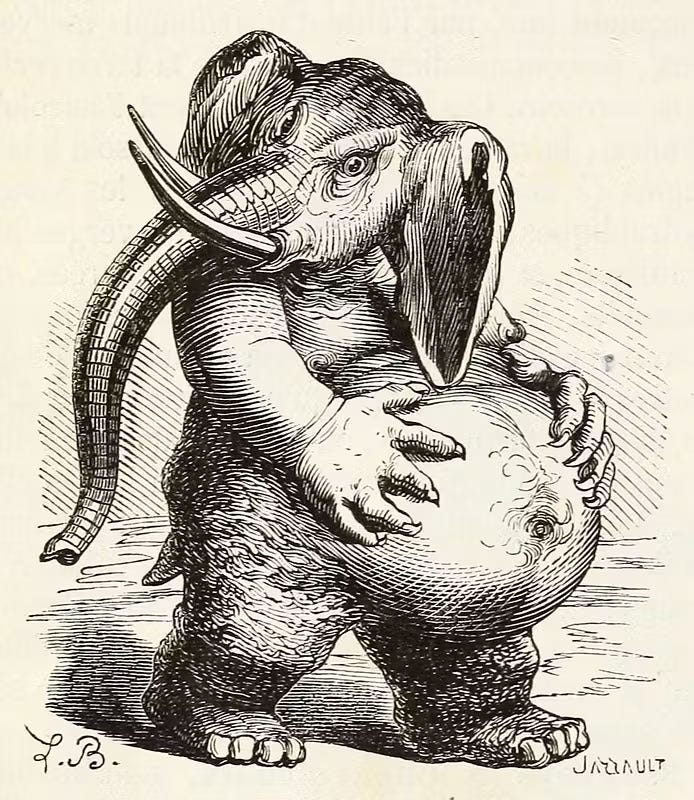

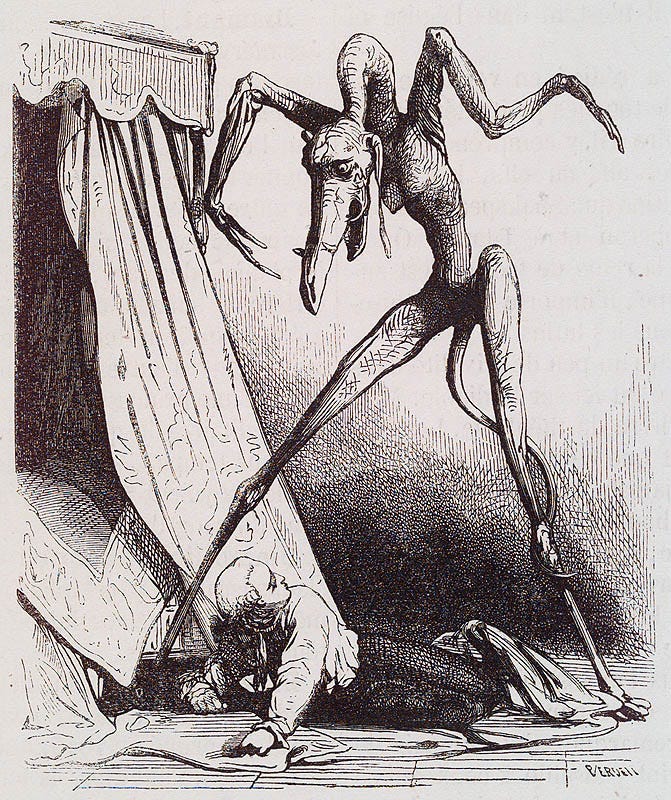

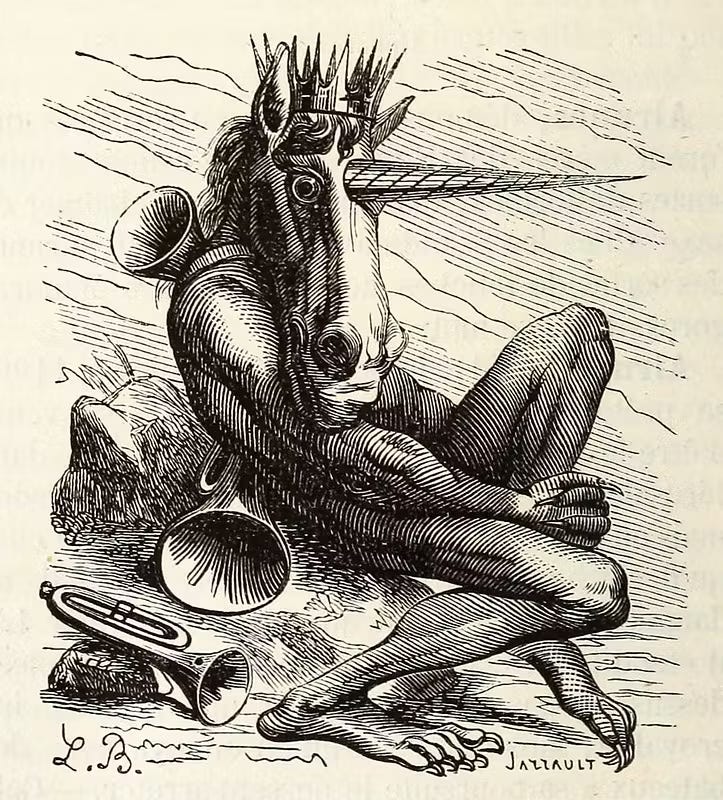

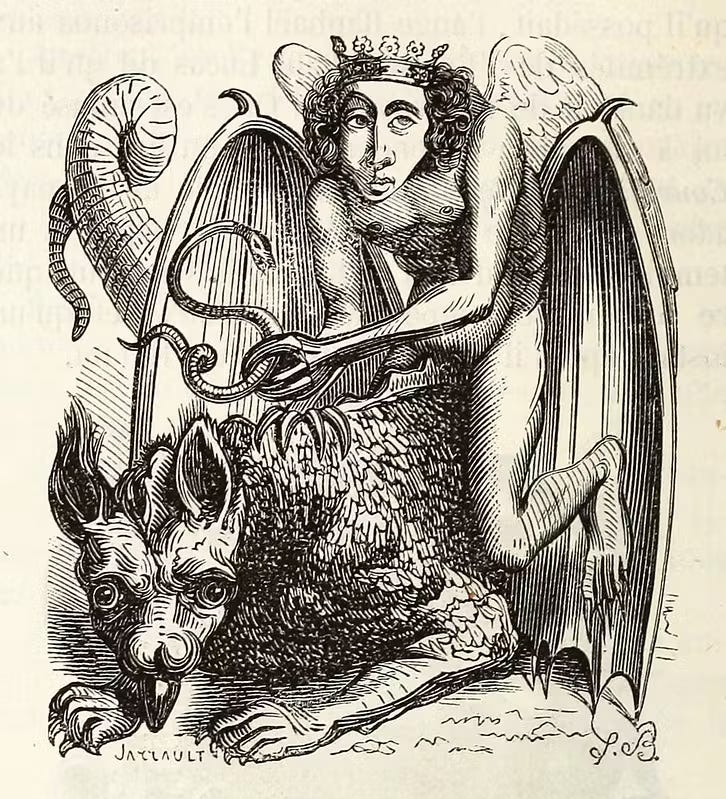

Until very recently, most Christians in the West believed, in the most literal sense, in the existence of demons. Demons existed on earth just as humans or serpents existed on earth. They existed in order to debase humans, who whatever their weakness and shame were created in the image of God; and they accomplished this through the arts of seduction. Those who fell under their power—those who lost themselves to temptation and made a bargain with them, who thought they could satisfy their deepest desires through that bargain—were gradually possessed by the demon, lost their humanity, became committed to the furtherance of evil on earth and in particular to the triumph of the seven deadly sins of Christian imagining: wrath, lust, envy, greed, sloth, gluttony, and pride. Demonic intervention in earthly affairs was everywhere present and was calculated to degrade humanity, to destroy all that was good and virtuous in human affairs, and to promote the brutish, the crude, the unconstrained.

Suppose for a moment that those old and superstitious people were right about demons. What force on earth today, one should ask, is committed to the promotion of the deadly sins of wrath, lust, envy, greed, sloth, gluttony, and pride? If Satan existed and created something on earth today, what would he create? One would imagine it would be something seductive, compelling, romantic, intensely interesting—Satan, as readers of Milton know, is charismatic and intriguing in a way God and his angels can never be. This demonic entity would offer the world to those it sought to corrupt. This demonic entity would present itself as the source of hidden truth, would reject the tired fogy moralism of the world—you actually believe that stuff? Don’t be a rube. Look at my Porsche. Look at my yacht. Look at the models I’m paying for one purpose or another. Look at my influence, my worldly powers. I have all of this: I am proud of what I have and rightly so. What do you have? Nothing. Aren’t you filled with envy? Good, that’s right, as you ought to be, you ought to be more like me; but it’s not my fault that the world has frustrated your hopes and ambitions and dreams. I am not the one taking from you what is rightly yours. Those people are. You would have all of this if not for them; you would have all the happiness that is denied to you if not for them. They want to crush you like an insect underfoot—you can crush them and rightly so. Do you sense that feeling of anger, that wrath? Embrace it. Let this hate, solid as stone, be my gift to you. Let it wash over you. And remember to like and subscribe.

Imagine that a wizard offers you a thin dark slab infused with magic. The slab offers you everything—all that is interesting and novel and strange, constant entertainment, constant titillation and stimulation, a sense of knowledge about the world, a sense of connection, affirmation. In your palm the slab is warm and comforting like the hand of another. You keep it close to you and let it whisper in your ear; if you look at it the slab offers you bright and colorful lights, lights that entertain you until you have grown accustomed to brightness and to color and no longer find anything in it worth contemplation. By contrast the world outside the slab appears increasingly dim and colorless and uninteresting. But with the slab you are never bored. From the slab you can hear the voices of friends and lovers. You spend your days with the slab, it becomes part of you, it becomes like an organ that grows out of your palm; you find the slab so entertaining, so engrossing, that you could never think of letting it go: it would be like severing a limb. When you wake up you look at the slab and when you go to sleep you look at the slab. When you have not seen the slab you crave it. In you it has become an instinct like hunger. Your spine has grown crooked to better look at the slab. It has changed how you speak, the words you use, the intonation of your voice, the ideas in your head. Soon the company of others—the company of awkward silences, unhappy truths about oneself or others, relationships that require tending like so many timid flowers—has lost its allure, and even when you find yourself around other people your slab with its comforting warmth and its bright colors and its endless stories is there for you. The slab whispers in your ears and tells you things about those you know, about your family, about your friends, disturbing things. Are they really your friends? Don’t lie: you have spent more of your brief life on this earth with the slab than with your mother or with your best friend. The slab is a better friend. It will be there for you no matter what. The slab does not speak unless you have spoken to it. Happily you devote your life to the slab. The best part of all is that the wizard did not ask for anything in return for this wonderful gift.

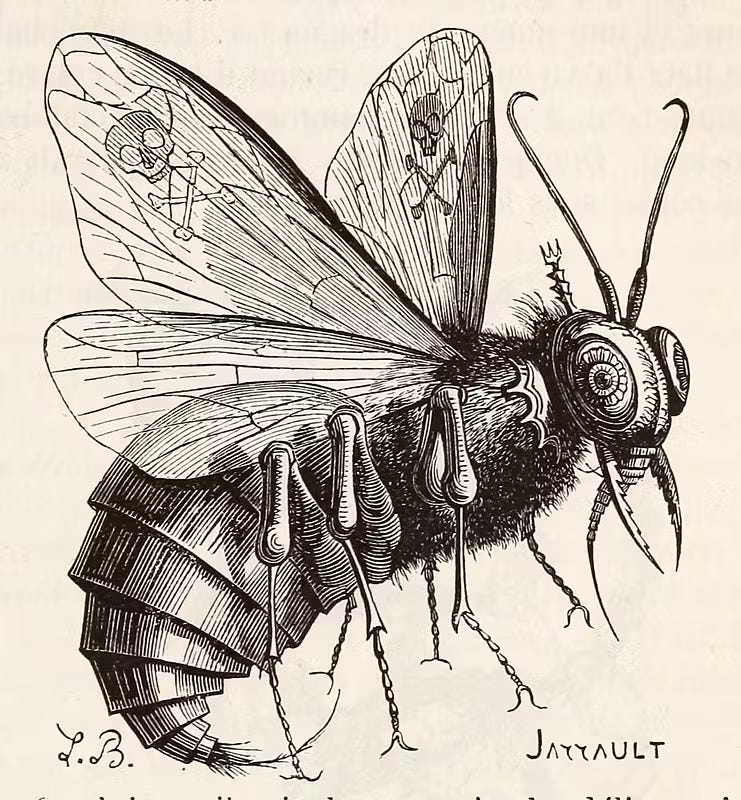

There is a type of insect called the Australian jewel beetle. The Australian jewel beetle has a black head and covering its thorax a long and golden-brown sheath with long striations like so many grooves in wood. In the deserts of Australia where the jewel beetle lives the men in their rough ways have a habit of throwing into the empty vastness small and fat beer bottles once they have been drained of alcohol. From this simple act of littering there emerges an unexpected dynamic among the jewel beetles. To the male jewel beetle, the beer bottle—golden-brown like it, unimaginably large and inviting, a mate more fertile than any actual jewel beetle could ever be—appears as the most attractive female that could ever exist. So aroused and stimulated and compelled is the male jewel beetle that the foolish bug will devote the remainder of its existence to copulating with the bottle. Many male jewel beetles will crowd on a single bottle, attempting to mate, pushing their organs against the dark glass without knowing that their efforts are doomed. So engrossing is this beer bottle that the jewel beetle forgets its own hunger and safety and after a long stretch of time spent attempting to give its life-force to the dark glass of the bottle the beetle will succumb either to hunger or to the relentless heat of the sun or to the predations of ants which consume this tragic beetle that, by something dark and unknowable within itself, even to the point of death is compelled to mate with this worthless piece of trash.

Once, when I was in college, I watched someone sit on a couch and scroll through TikTok. Against the long inexpressive slab of his face the lights of a bedroom in Perth or Akron or Birmingham, young girls in overlong shirts offering to the impassive eye of the camera their mating dance, robotic voices that begin and end as the impassive eye of the human viewer watches the dark glass in utter silence. “That feel when.” “You know it’s.” “My dad just.” The viewer scrolls again and evinces neither interest nor joy in anything he sees. His visage is blank and disinterested, his eyes cloudy and vague. He lies on his back like a vast distended beetle. From the black slab across from his face only a gurgle of meaningless noise.

Leonard Cohen said, “I have seen the future, brother, and it is murder.” On days when a man is shot in the neck and his throat explodes in a torrent of blood that wets his shirt and he topples over lifeless, and the video of his death—the extinguishment of this human life however imperfect it is as all human lives are destined to be—is shared endlessly by friends and by enemies and by people who care little but have some morbid desire to see a video of this prominent man dying in a blaze of mortal splendor, on days when we all consume the media of his death for purposes that are something like entertainment, on those days I agree that the future is indeed murder, that the blizzard of the world has crossed the threshold and overturned the order of the soul, that social media—this cacophony of voices without a face—turns us into beings so debased as to verge on the demonic. I am enough of a product of our disbelieving age that I cannot bring myself to accept that demons literally exist, that they exist to tempt and pervert us; but I believe that the human spirit can grow so impoverished and wretched as to make demons superfluous. Writing on Dante’s Inferno, the poet T. S. Eliot wrote that hell is not a place but a state, a state defined chiefly by solitude; in hell we are alone and just as there is nothing to which we can escape there is nowhere from which we are escaping. For Eliot the key fact about hell is that whatever we might think the other figures present to us in hell, the demons who torture us, are mere projections; there is only us, alone with ourselves and our dim thoughts and our sad conscience. It is this basic loneliness that seems to be the defining feature of the communications technologies that have conquered social existence. Social media offers to us a simulation of social life, but one bled of connection to the real world and thus of the compassion and responsibility that undergirds communal existence. At the end of the day, whatever we might tell ourselves—that by staring at the dark glass of the screen we are revolutionaries, communists, fascists, that we are saving the republic or ending it, that we are saving humanity—we are left alone only with the truth of ourselves, with the truth of damaged life, with the truth of silence.

Yes and the printing press was just people twirling mark making knobs without action in the real world. Note the arrival of that technology involved a lot of upheaval until new institutions emerged...

This post is masterfully written, and we all know the place this cri-de-cœur is coming from.

Yet, readers enchanted by this waterfall of words should reflect on the fact that mere 250 years ago people would willingly gather to watch a hanging of a 13 y.o. indentured servant who stole a few coins from his master, and think the whole thing righteous and just, not to mention entertaining. They would come and watch in person, no magic slab needed.

Before the rise of the slab, if an army supported by taxpayers' money wantonly slaughtered a villageful of men, women and children in a faraway land, said taxpayers would likely know nothing of it; there would be no outrage, no massive protests (except perhaps to put an end to the draft).

Also, it is good to remember that the worlds hidden between the covers of many books are just as magical and addictive as the slabworlds - take it from someone who has recently stayed up, book in hand, till 2 am, perfectly aware of the misery the next day would bring, yet unable to put it down.

So:

the slab is a window, but it is also a mirror.

It is a multitool, like a kitchen knife, and should be used with caution. Yes, we need to talk to our kids about the dangers of the slab - like we talk to them about alcohol, drugs, guns, and bad people.

The world has always been a violent, dangerous place. Snuff videos are disgusting. But let's keep in mind that public executions that they have replaced were infinitely worse.