The crisis of central banking is structural

Fiscal dominance is our future

Tyler Cowen wrote a good post yesterday about central bank independence in the United States. I want to focus on an important point that Tyler makes, which is that the current period of tension between the federal government and the central bank has structural roots beyond the president’s whims. As Tyler writes, “the Fed is most ‘independent’ when the stakes are low and most people are happy with (more or less) two percent inflation. That is also when the independence matters least.”

Indeed, with the benefit of hindsight, it is clear that between the early 1980s and the late 2010s central bankers enjoyed a golden age of independence and prestige that was rooted in fundamentally favorable macroeconomic conditions. That happy period has now ended, and we are entering a different world.

The Great Moderation of those decades—the long period of relatively tame inflation and low unemployment which made the job of central bankers relatively easy—owes some debt to the increased independence that central bankers enjoyed after the interest rate shock engineered by Paul Volcker. But we shouldn’t give the central bankers too much credit for the benign macroeconomic environment of those decades. A variety of positive supply shocks, most importantly the addition of the massive Chinese and Eastern European workforces to the global labor supply, ensured a long run of price disinflation. These positive shocks provided economic tailwinds of higher growth and lower inflation that made the jobs of Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke much easier relative to the thankless tasks of much-maligned Federal Reserve chairmen of the 1960s and ‘70s like Arthur Burns.

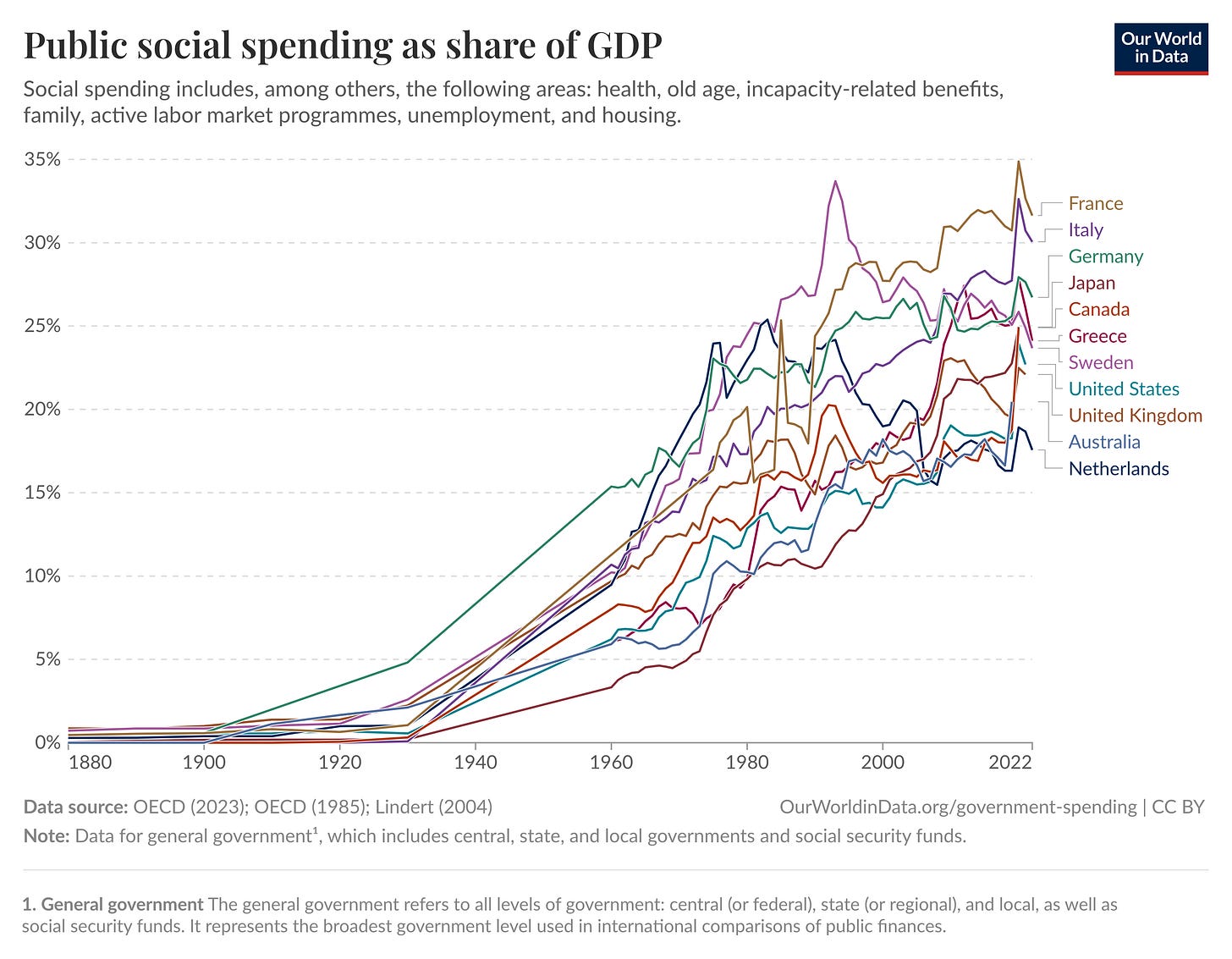

That prolonged disinflation has now run its course. Every rich society faces the same crisis of sluggish growth and an increasingly old population that demands an ever-larger share of societal resources. As has been argued by Manoj Pradhan and Charles Goodhart (of Goodhart’s law) in their excellent book The Great Demographic Reversal, this is ultimately a simple issue of fewer producers and more consumers. Insofar as inflation is a matter of how much is produced and how much is consumed, the increasing share of elderly people who consume but do not produce will create a secular trend toward inflation (particularly for non-tradable goods like services), profound fiscal stress due to the increasing share of public resources allocated to the elderly, and lower economic growth as spending shifts to the consumption of labor-intensive, low-productivity services like healthcare. That is more or less what is playing out in the United States, Europe, and other rich countries as a structural consequence of low fertility rates, low productivity growth, and increasing life expectancies.

Because most rich countries have at the core of their political settlements an inviolable concession of public resources to the elderly, this has particularly brutal fiscal consequences. As every rich society has grown much older and healthcare costs have increased due to Baumol effects, redistribution to the elderly has become the bulk of government spending with no concomitant increase in societal resources to pay for it. Because of the political power of old people, these commitments have thus far proven to be politically untouchable in every rich society.

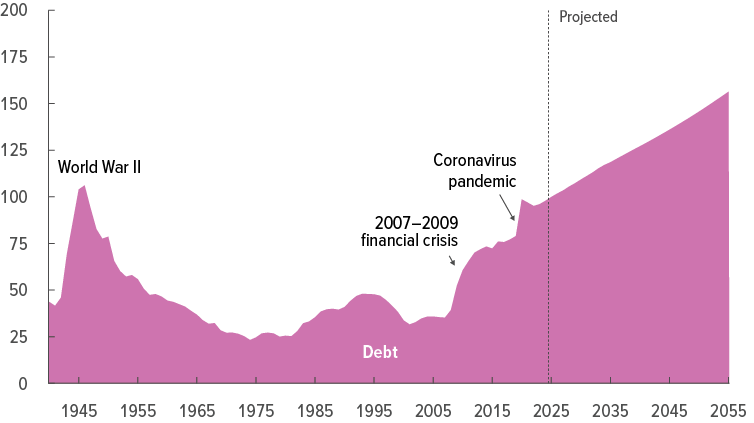

From the perspective of the central banks, this creates a cruel bind. The core idea of monetary policy is that inflation can and must be met by monetary intervention, chiefly in the form of higher interest rates. But as rich-world governments allocate more and more of their fiscal capacity to redistribution in favor of the elderly, deficits and debt loads will increase and sensitivity to interest rates will grow. The fiscal deficit that the United States runs each year, for example, has increased from 1.4 percent of GDP in 2002 to 6.3 percent in 2023; accordingly total public debt has risen from about 55 percent in the beginning of the century to more than 120 percent by 2025, comparable to its historic peak during the Second World War even in conditions of peace and prosperity.

This, in turn, means that interest expenses will consume a greater share of government spending. In 2024, for the first time ever, the U.S. government spent more on interest payments on its debt than on the military.

This means that absent drastic fiscal reform, eventually every country in the “rich and old” category will face some version of what a famous 1981 paper by the economists Thomas Sargent and Neil Wallace called “fiscal dominance.” By this Sargent and Wallace mean a situation in which extensive fiscal commitments severely limit the ability of the central bank to manage monetary policy. If the path of fiscal deficits is taken as given and these deficits can only be financed by debt or seigniorage (i.e., money creation by the central bank), any shortfall that cannot be covered by debt must be covered by money creation.

In these circumstances the central bank will lose the ability to effectively combat inflation. If it raises interest rates to combat inflation, it will only increase the long-run costs of government debt and thus increase the fiscal deficit; absent future fiscal surpluses, that increase will have to be covered by future money creation, implying higher future inflation. Anticipation of higher future inflation, in turn, should serve to increase inflation now. In extremis this will mean that the central bank becomes impotent in fighting inflation.

One need not accept the exact assumptions that Sargent and Wallace make for the basic dynamic that they outline—large deficits and high inflation make it much harder for central bankers to combat inflation—to make sense. It might be that the mechanism by which central bankers lose their independence is more crudely political: while central bank independence is generally protected by statute in the United States and other rich countries, as Cowen says in reality central banks have always been accountable to politicians and to the public. The only things stopping the most overt forms of political influence are a cultural norm of deference among politicians and of professional obligation among central bankers. Those norms emerged only in benign, disinflationary conditions; before the Great Moderation, presidents like Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon were more than willing to place immense pressure on the Federal Reserve to do their bidding. In an atmosphere of inflation and deficit, it is not hard to imagine a return to that more vicious world.

So expect a structural tendency in which central banks are leashed to fiscal considerations. Absent drastic reforms or a huge increase in labor productivity, what Ken Rogoff calls a “new era of fiscal dominance” is our future. But like financial repression aimed at the private sector, constraints on central banks is only one of many ways that increasingly desperate fiscal authorities across the rich world will attempt to externalize the costs of a basically untenable political-economic settlement in which a massive share of resources are allocated to the elderly. At some point that bill will come due.

Perhaps such conditions also limit the ability of central banks to suppress consumption through interest rate rises as the elderly are not as sensitive to increased interest rates as the young/businesses.